To say that Barbie has become ubiquitous is not an understatement.

We’re just short of the Barbie movie hitting theatres (July 21) and it’s been a non-stop Barbie blitz. The trailers for the film have sparked endless memes, parent company Mattel has partnered with more than 100 brands to market the movie, and embracing of the film’s aesthetic has caused #Barbiecore to trend for months on social media.

It’s becoming clear that the Barbie movie will likely be a raging success. Even if one were to set aside the star-studded cast (Margot Robbie, Ryan Gosling, Simu Liu, etc.) and big-name director (Greta Gerwig), the intense and over-the-top Barbie bombardment for the past six months shows no signs of slowing down, and most people seem to be more amused than fatigued by the piling on of pink.

But dark shadows linger over the Barbie brand, and some are baffled as to why the world is so willing to look beyond the doll’s problematic past and gaze at Mattel’s onslaught through rose-coloured glasses.

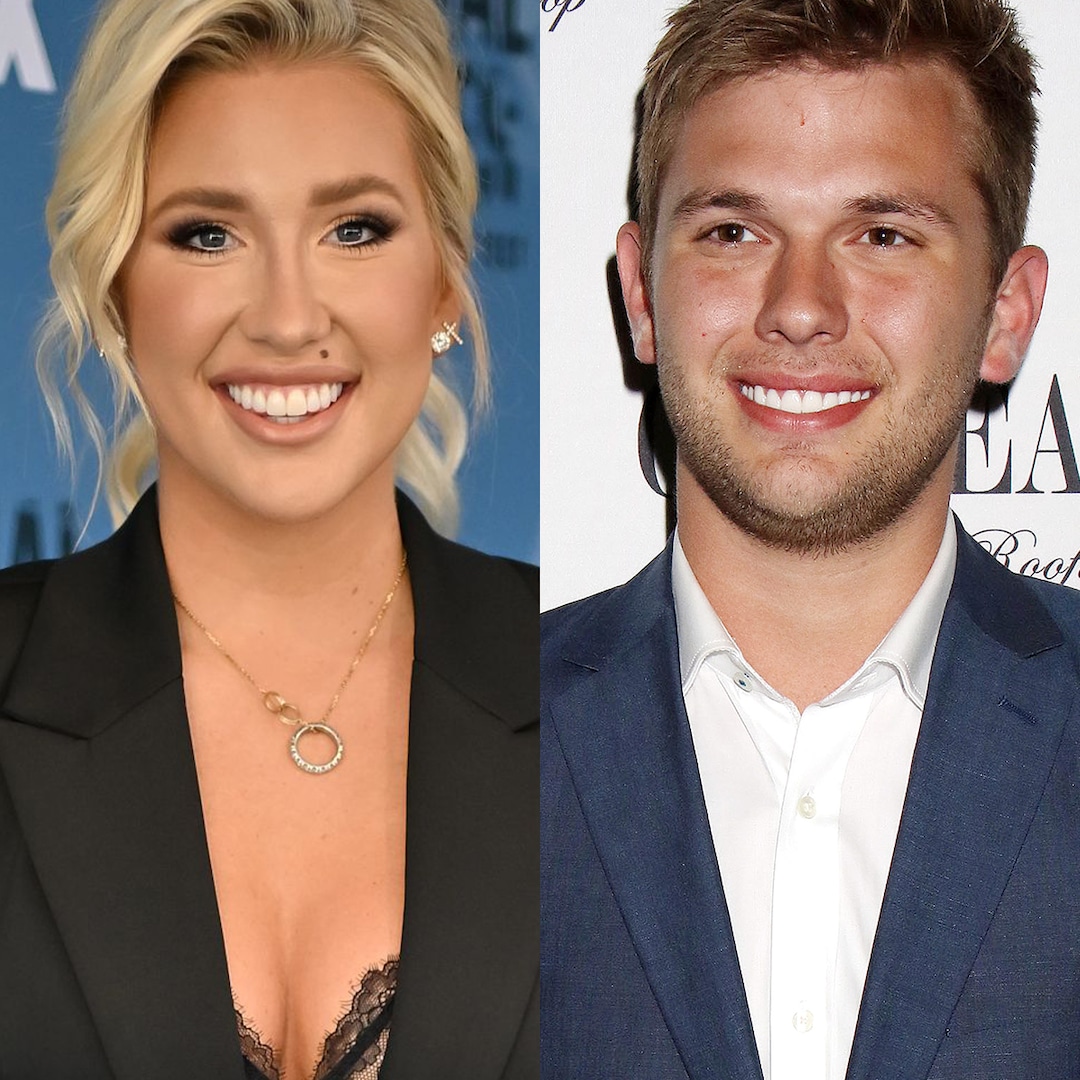

The problems for Barbie started right out of the gate. The first iterations of the doll’s design in 1959 were inspired by the Bild Lilli doll – a racy, buxom doll marketed to German men and sold in adult stores. In her origin as a cartoon strip character, Lilli was known to be a gold-digger with an oversized bust and was often portrayed in sexy clothing, giving snappy comebacks to drooling men.

The Bild Lilli doll is based upon the cartoon character Lilli created by German cartoonist Reinhard Beuthien for the newspaper Bild-Zeitung, Hamburg, Germany.

SSPL / Getty Images

And while Mattel’s design team softened the face and body of Barbie, she still wound up with unrealistic proportions — a woman of Barbie’s weight, combined with her hip-waist-bust measurements, would not be able to stand up without tipping over, nor would she be able to menstruate, said doctors.

For this, Barbie’s been accused of perpetuating unrealistic beauty standards and promoting gender stereotypes. And while Mattel, in more recent years, has attempted to deliver more inclusive Barbies — in 2019, the company introduced Creatable World, its first series of gender-neutral Barbies, while three years earlier, it launched Barbie Fashionistas that came in four body types, seven skin tones, 22 eye colours and 24 hairstyles — the company has also played directly into the narrative.

One of her more scandalous moments came quite early in her history when a 1963 teenage “babysitter” Barbie was sold with a doll-sized diet book titled How to Lose Weight: Don’t Eat. In the 1990s, critics were incensed over a talking Barbie who came pre-loaded with a ditzy declaration: “Math class is tough.”

(Simpsons fans might also recall a 1994 episode about Malibu Stacey, the show’s answer to a Barbie doll, who famously proclaimed “Don’t ask me, I’m just a girl!” when her cord was pulled.)

It’s tough to measure if Barbie has affected children’s body image or self-worth, or if they’ve internalized any of the unrealistic beauty standards of Barbie at all. Most studies on the topic have been conducted on small groups of girls and have yielded lukewarm results.

Some researchers claim that Barbie is just one of many influences in the lives of young girls that prioritize and encourage rail-thin figures in western culture. Others are critical of these studies, saying that research conducted on girls nearing puberty is skewed, as it’s this time in a girl’s life when she becomes more critical of her physicality anyway.

Even attempts by Mattel to be more inclusive have backfired. In 1997, Mattel released Share-a-Smile Becky, who was the first friend of Barbie to use a wheelchair. It turned out that Becky’s chair couldn’t fit through the door or into the elevator of the Barbie Dream House, leaving her destined to sleep on the porch.

That same year, a collaboration project between Mattel and Nabisco resulted in a massive recall when it was brought to attention that “Oreo Fun Barbie” — a Black doll with an Oreo-branded outfit and cookie purse — was derogative to the Black community, as “Oreo” has been used as a racial slur.

Still, those coming to Barbie’s defence, including Mattel itself, will point to Barbie’s progressive and feminist career trajectory over the years. Over the years, she’s held hundreds of careers, including when she “broke the plastic ceiling” and travelled to the moon in 1956 (four years before Neil Armstrong), ran for president, and held esteemed jobs like computer engineer, paleontologist and rock star.

Barbie has held hundreds of jobs over the years.

Mattel

But, again, Barbie as a working woman has faced her share of hiccups. As recently as 2010, Mattel faced backlash when a companion book included with Computer Engineer Barbie showed the main character infecting her computer with a virus and needing her male co-workers to help her get the problem sorted.

Through a complicated combination of missteps, adults projecting various stereotypes and mores onto Barbie and a surge in alternatives in the doll market, Mattel was left with plummeting sales and interest in the Barbie brand by the mid-2010s.

“Back in 2014 and 2015, we hit a low and it was a moment to reflect in the context of, ‘Why did Barbie lose relevance?’” Ricard Dickson, Mattel’s president and chief operating officer, recently told CNN.

“She didn’t reflect the physicality, the look, if you will, of the world around us. And so we then set a course to truly transform the brand with a playbook around reigniting our purpose.”

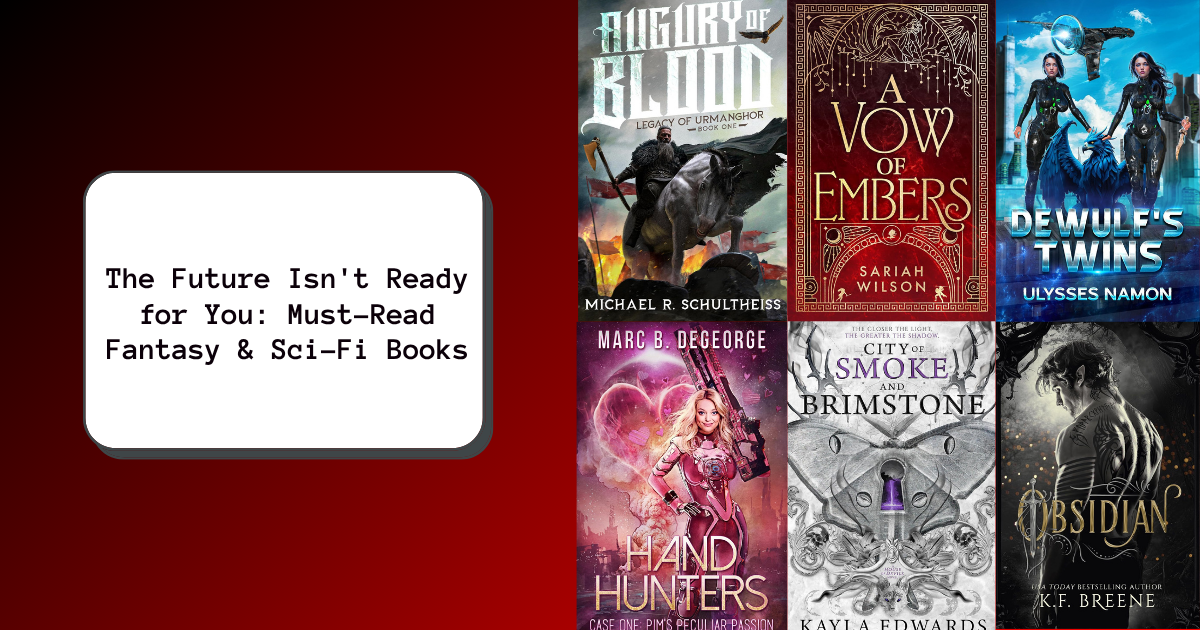

Mattel told CNN its hope is that the Barbie movie will give its brand a boost. While sales for the doll were up during the pandemic, they slumped again in the first quarter of 2023.

Ryan Gosling and Margot Robbie attend the red carpet promoting the upcoming film ‘Barbie’ at the Warner Bros. Pictures Studio presentation during CinemaCon, the official convention of the National Association of Theatre Owners, at The Colosseum at Caesars Palace on April 25, 2023 in Las Vegas.

Greg Doherty / WireImage

And while it’s too soon to tell if the movie will boost Mattel’s bottom line, the company is likely gleefully watching the hype surrounding the movie. The internet is awash in anticipation of Friday’s release and the reviews are, for the most part, positive. A movie version of the doll has sold out, and on Wednesday it was announced that the film has the most ticket presales since Avatar: The Way of Water.

The stars and director of the film, too, have painted the movie as a tongue-in-cheek look at Barbie’s history, the brand’s misfires, as well as the rhetoric surrounding the doll since her conception.

Gerwig also committed to casting a critical lens on the patriarchy and set the Barbie movie in a world where women are in charge — for example, Issa Rae plays President Barbie, and Barbie Land has all women justices on its Supreme Court.

“I think in a lot of other hands, a Barbie movie would remain surface level. But I knew Greta (Gerwig) was going to have a lot to say, and I knew she was going to Trojan Horse a lot of… big issues within a very fun world,” Margot Robbie, who plays the titular role, said.

Mattel’s strategy over the years to make the Barbie brand more diverse and inclusive will also be reflected back to audiences through the casting choices, said Robbie.

“I hope people walk away… I hope that they feel good about themselves watching it,” she said. “I feel like there’s some sort of relief in this movie and that the message ultimately is, ‘You’re good. You’re good as you are.’”

No matter how you slice it, Barbie has always been — and will continue to be — a lightning rod. Debates surrounding her moral and social significance will continue to rage, no matter how many new dolls or movies are put out into the world.

For some, she will continue to represent all that is wrong with beauty ideals and capitalism, while others will continue to hold her up as a conduit for the dreams and aspirations of young children.

Just as real women are policed every day for their bodies, their dreams, how they act and what they achieve, so, too, will Barbie.