In 2023 I traveled to Qaraqalpaqstan, Uzbekistan, to chase the remnants of the Aral Sea. In a hurry, I packed winter boots to protect my feet from the burning ground, a wide hat, a camera and a sketchbook, then boarded the plane without fully processing where I was going. But soon after arriving in Moynaq, when we drove beyond the last houses in the village and the road opened into nothingness, the emotions overwhelmed me. The horizon was a straight unbroken line in every direction. No sound, no wind, no sign of water or life. I realized I was standing on the exposed dry surface that once was one of the world’s great lakes. The heat radiated through the soles of my boots, the ground cracked beneath me like dried clay. In that silence I felt both awe and unease, and the awareness of how small humans are beside nature, and how much damage we are capable of leaving behind.

Before traveling, I went through my mother’s old photo album. In the early pictures from the 1960s, she is a smiling child standing with her grandmother, before long days of picking cotton in the fields. She used to tell me how every fall, children were taken out of school to harvest “white gold.” Meanwhile, far from the pages of her album, the Aral Sea was already beginning to shrink quietly. I never connected her childhood stories to that disappearance until much later. Standing in the Aral Desert, I remembered those black-and-white photographs and grew cognizant of time moving forward while something essential slipped away in the background.

During my own childhood, the Aral Sea felt distant and abstract, a place we rarely saw in pictures and never visited. Sometimes experts on the news would mention its decline, but it was hard to grasp. The sea seemed too vast and mighty. I couldn’t imagine that something so big could vanish almost overnight.

Only as an adult, and now as a parent to a daughter almost the age my mother was in those photographs from 1963, did the stories from her generation and mine begin to align. Standing on a dry cracked surface that once held water, the loss no longer felt abstract or distant. It felt personal, intimate, as if a part of our family’s story had vanished along with the sea.

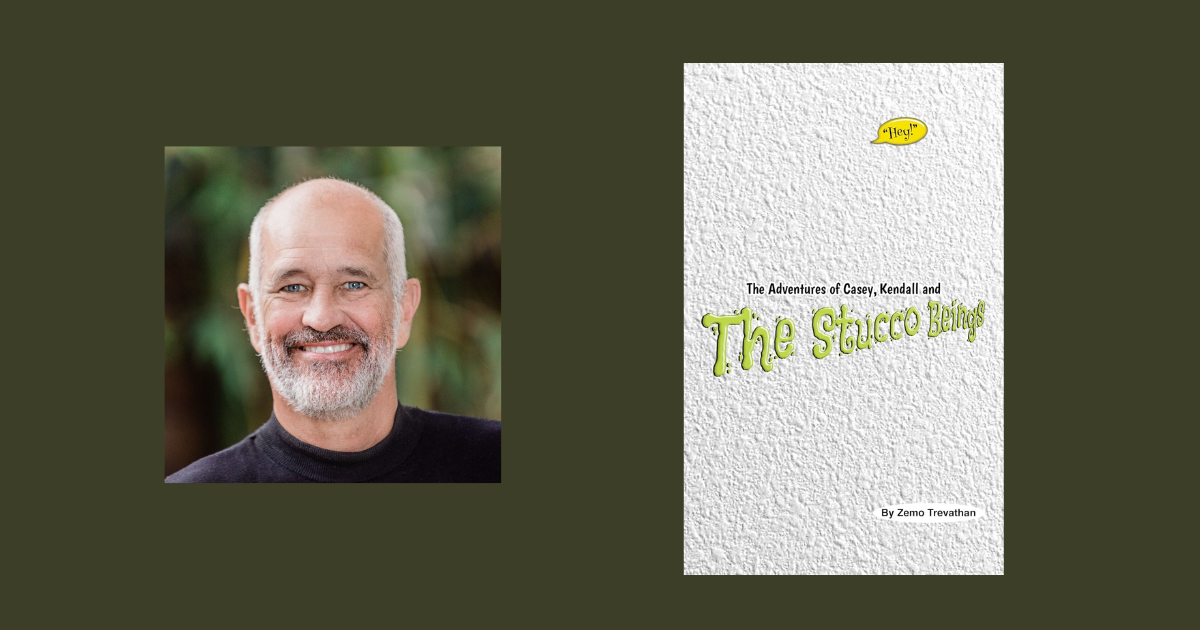

As an illustrator, the first things I noticed about the Aral Sea were the colors and textures. I liked the way the cracked ochre ground coexisted with the bright ultramarine sky. I wanted to translate that silence into images, as if drawing could preserve what the water once held. I thought about my daughter’s generation, too, and how they would know this place only through stories, not memory. That thought stayed with me long after I left, and slowly it began to take the shape of this book.

What I hope young readers feel when they turn the pages of The Vanishing Sea is not grief, but a sense of connection to a place that once held so many stories and lives. That’s why the book moves like a quiet folk ballad, where the ultramarine meets the ochre. If children can still feel it, then the sea is not entirely lost.

Author photo by Audrey Jones