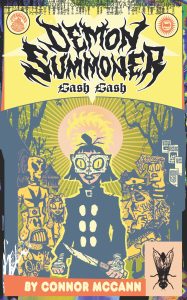

Cartoonist: Connor McCann

Publisher: Strangers Publishing / $25

June 2025

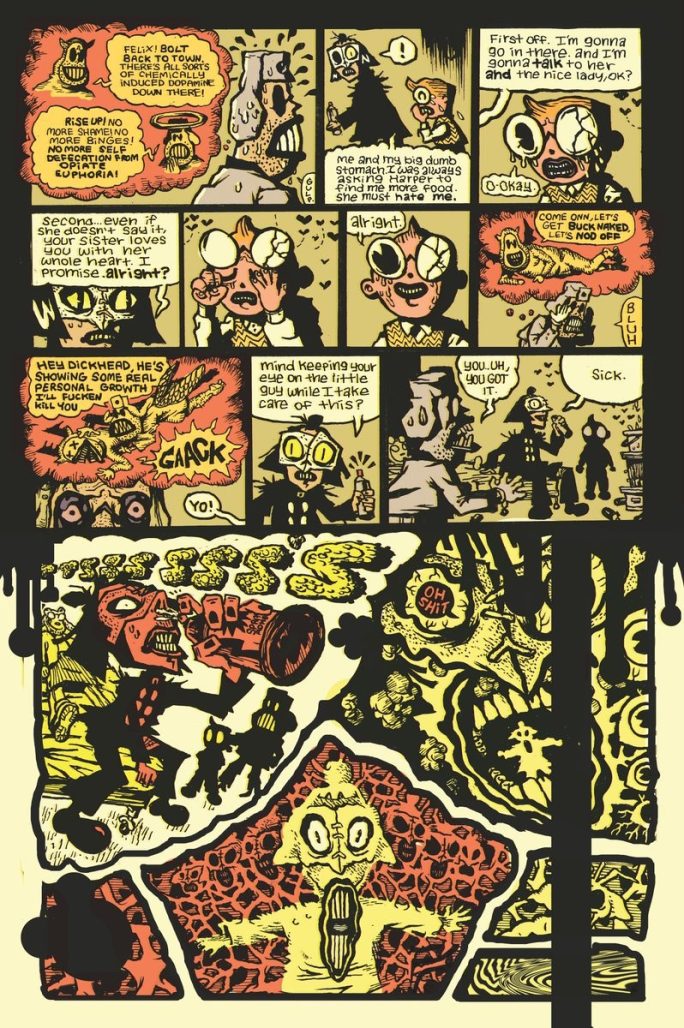

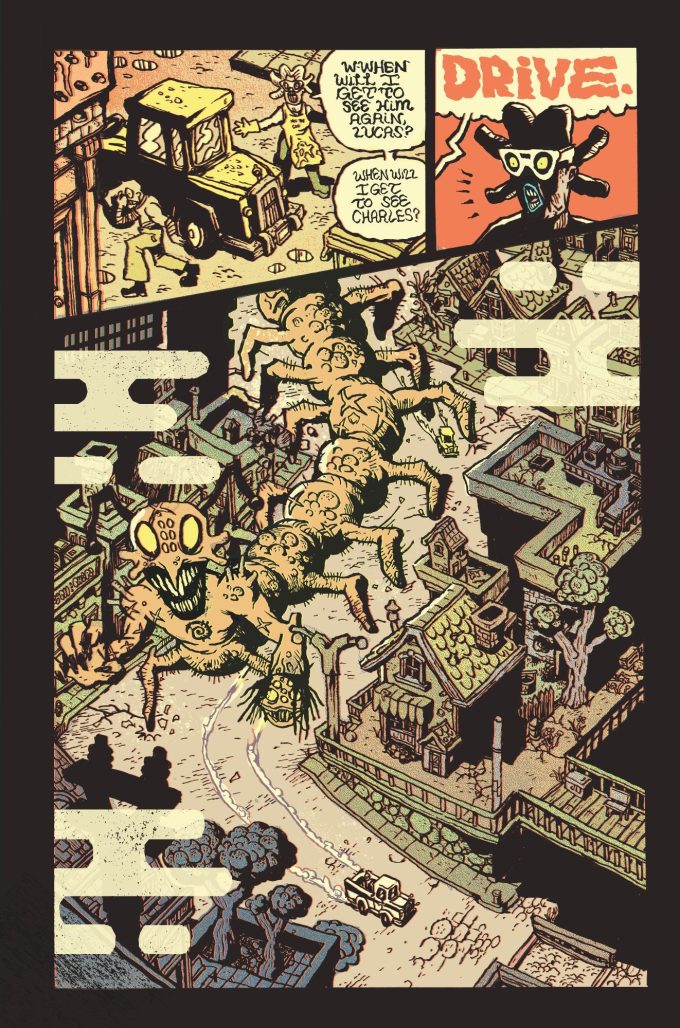

The end is coming for Mason and Matilda. The end is here already, actually, and has come many times since. After the flood were the demons. Once upon a time, the siblings sought to be powerful protectors, but fast forward past some unspeakable horrors to today, Demon Summoner Gash Gash, and they’re both kind of a shambles. Mason’s still at it, being a scumwitch, making deals with lesser evils to fight against greater ones, a mutilated shadow of his former self (in body, not spirit). Matilda’s got a job in the service industry and goes to bed most nights so hungry she can’t think. Neither are ready for what the mind of Connor McCann has in store for them: the ascension of the Centipede Golgotha.

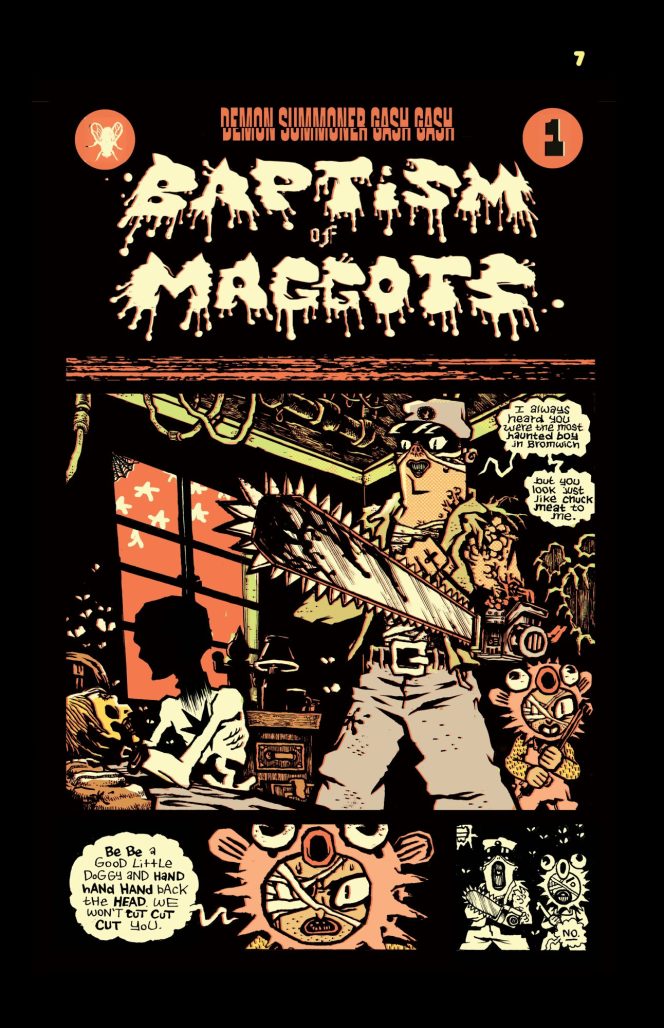

So of course the way it looks is nightmare cartoons. Cherubic, big eyes with tiny smiles and apple cheeks. The moon that the cow jumps over. Wide thick limbs and a little potato body. The weird and wild days of sweet, smeared animation before the era of the mouse. Only in Bromwich Bay everyone’s got boils and stubble and wrinkles and sweat beads and blood spatter and is full of ropes and ropes of intestines. Big hands and crooked teeth. Dancing shadows. Everything is so dark; there’s so much black ink on every page, crowding around the panels as well as flowing into them, and such a small amount of light for these goofy little witches to fight for.

The back cover of the Strangers Publishing edition- part of the same release slate as The Hanging– cites Go Nagai as an influence (and Cormac McCarthy and Gummo), and yeah. Something like Centipede Golgotha, I can see it. I actually really like the scumwitch attire. Mason’s take somewhat Grendel and kind of Super Sentai. Matilda’s mask gets me thinking Phantom of the Paradise. But all this to say, the character design is on point, and even gives a little weight to the idea of it being a hero’s story. Check out the demon who runs the pawn shop, a genial clown with far too many arms. The prosthetic head may be empty, and yet parts of him are around everywhere, under tables, in shadow. Even more insectoid are his children. The flooded out hell town was pleasantly quirky before the ruin. Now what hasn’t been puked on is covered in maggots. Every other resident seems to have an eyeball dangling from the socket. You can imagine the local karaoke bar.

Even in Hell, domesticity persists. One can’t properly face the apocalypse with nothing in the belly save dumpster-bound scrounged pub grub. In-over-your-head demon debt that starts with cutting off fingers and only gets worse, all to get out from under modern normal debt? Honestly, I have read less believable comics. Poverty and desperation, family and sacrifice, these are themes that run through the book, appearing in many ways. Subtext, and sometimes text, but also not binding. Is Demon Summoner Gash Gash anti-violence? It doesn’t seem like it. Rather than McCann sewing it shut for us, the reader is who reconciles the humanity of the characters with the actions they take, the world they live in.

McCann achieves something a great many illustrators, cartoonists, and game creators are trying very hard to do. Cute gross. Beautiful ugliness. Unfamiliar nostalgia. More than that, the conventions Gash Gash engages with exist within a broader intention of storytelling from McCann than the shock of upset expectations. Pastiche can be a fence that corrals a story’s potential. Gash Gash follows the path, it delivers the mythic thrills that Rank and Raglan promise, but is bigger than ending with something as easy as a victory. Violent confrontation is to be expected. It happens every day, to nearly every resident of this cursed, flooded pit. What makes one brawl different from any other?

Demon Summoner Gash Gash answers the finality of death with the unpredictable weirdness of life. Life is an ever-mutating, marvelous disaster, and despite their methods being submerged in blood, that’s the side a scumwitch fights for. It’s sanguine violence paying homage to martyrdom. There’s a contradiction for you. And yet, James O’Barr’s The Crow. It’s about revenge, about making deaths with things beyond that cause suffering to cause suffering, about losing someone, wanting to protect them, feeling like a failure, being drawn into your worst behavior despite your intentions.

So it’s not about the body suffering. Gash Gash is torturing the spirit. The scumwitch stays alive despite each pound of flesh sold. The suffering endures. This is about what the Matilda and Mason are undergoing, “twin infinities of love and horror,” a deeper pain than loss of limb. The violence and aesthetic and even the situations can be absurd, their relentlessness is not. Who hasn’t been trapped in an awful conversation while running an errand? Feel for these folks, though, that will get you in trouble.

Demon Summoner Gash Gash is published by Strangers Publishing.