In the first half of the year, Scowl entered their sophomore season with Are We All Angels. Made with Will Yip, the album captured the Santa Cruz band stretching further into the alt-rock realm while continuing to carry a hardcore mentality (vocalist Kat Moss, guitarist Malachi Greene, and drummer Cole Gilbert met at 924 Gilman in Berkeley and formed Scowl a year later). Moss bounces between bright pop melodies and throat-shredding screams, overcome with grief, burnout, and trauma from spending the past couple of years on the road. “The only way that I found to survive it was to check out, disassociate, and just have my physical body show up,” Moss said in an interview, recalling a 2023 tour with Militarie Gun and MSPAINT where she was sick most of the time. “It’s this dream-like experience while also feeling like the fire of hell.” Appropriately, Are We All Angels is the sound of a band who have reached their limit but find the strength to swing through the other side, continuing to expand what punk can be in the process.

Though they came up in the Bay Area hardcore scene, Scowl aren’t shy about their wide-ranging tastes, citing My Chemical Romance, Julien Baker, Sonic Youth, and, naturally, Fall Out Boy as their guides. Gilbert, in particular, has been listening since he was 8 or 9 years old, calling Take This to Your Grave one of his favorite records of all time.

Read more: 15 of Fall Out Boy’s heaviest songs of all time, ranked

Of course, Fall Out Boy’s own roots stemmed from the hardcore and punk underground of their native Chicago. They formed at all because Pete Wentz and Joe Trohman were burnt out on hardcore, seeking an escape from the seriousness of their former band, Arma Angelus, and the scene at large, so they channeled their energy into a new project. The pieces started to fall together when Trohman met Patrick Stump at a Borders in Wilmette, turning an argument about Neurosis into a lifelong friendship. As Trohman detailed in his memoir, None of This Rocks, he told Stump about the band, encouraged him to audition, and blasted through songs on Saves the Day’s Through Being Cool to gauge chemistry.

After they made 2003’s Evening Out With Your Girlfriend — a project that Trohman calls an “embarrassingly bad pop-punk time capsule” — they knew they needed a proper drummer, Wentz’s former Racetraitor bandmate Andy Hurley, to redefine and expand their sound. “He’s the guy we wanted all along — easily one of the best drummers in the Chicago and Milwaukee hardcore scenes combined,” Trohman writes. “Everyone wanted him in their band. I’m not even sure how we landed him in our early incarnation of Fall Out Boy. Did I mention we were abysmal? Andy made us better. His solid backbone drumming made us want to be a better band. Soon after he joined the fold, we tightened the hell up and wrote new songs. Good songs. Songs we weren’t embarrassed about. In fact, we were thrilled about them.”

Through the years, the band have transformed those gritty roots into bona-fide pop-punk hits, music videos with Kim Kardashian, and collaborations with Jay-Z and Elton John. They’ve never been afraid of change, daring to call it quits before recording the same album twice — a path that Scowl also seem ready to follow.

In the months following Scowl’s Are We All Angels, Gilbert connected with Hurley over Zoom. Together, the duo fell into a lengthy conversation about their favorite players, advice for fledgling drummers, and the ways hardcore has grounded their lives.

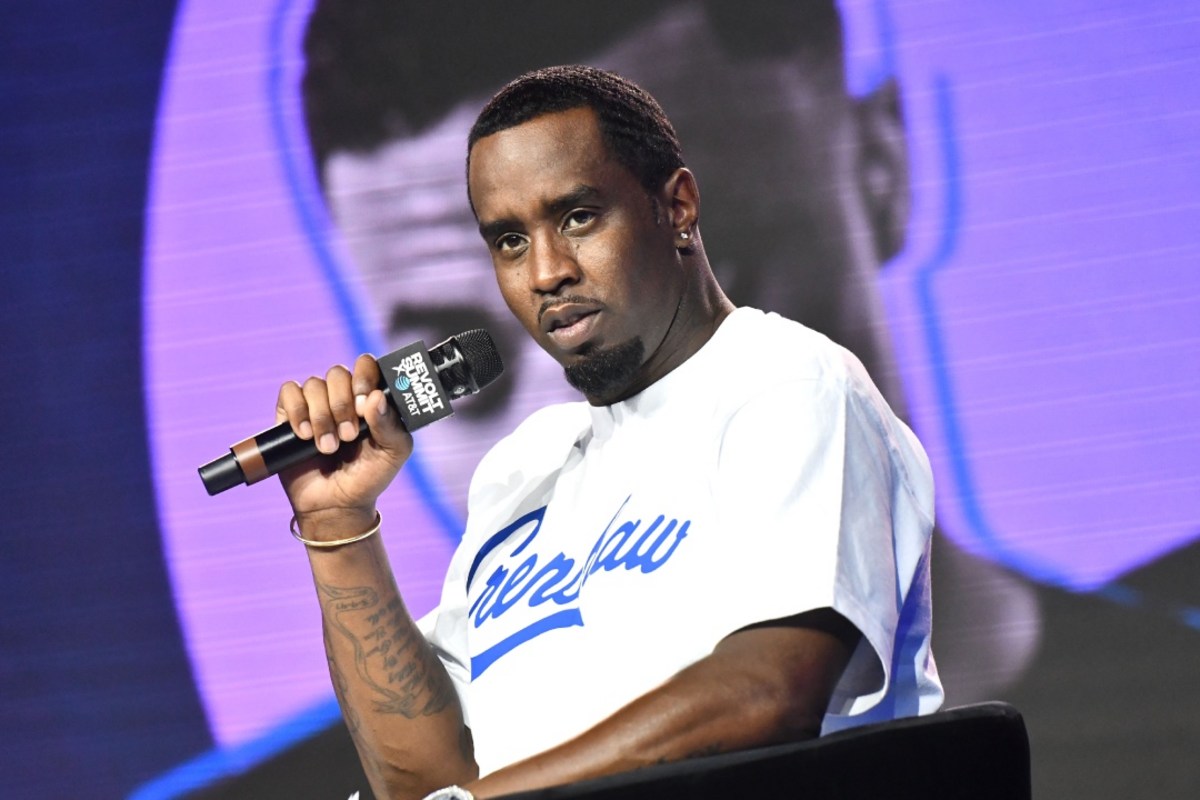

Shirlaine Forrest/WireImage

COLE GILBERT: I am very heavily influenced by your drum performance — literally across your entire career. You’ll hear the question asked, “Who do you try to emulate?” There are plenty of drummers I like, but I just try to play like myself. But if I had one person, one specific influence, especially with Scowl, I’d say it would be you and your drumming, quite a bit. There are a few parts where I listen back to our new album, and I’m like, “I know exactly where I took that from, be it subconsciously or consciously.” One of the singles on our new album, I completely ripped off a part from MSPAINT, and I’d had no idea until I listened back after recording.

ANDY HURLEY: Well, first of all, I’m totally honored. The way I look at drumming, there are templates. If you’re in a crust-punk band, you play a D beat. If you’re in a black-metal band, you’re going to be playing blast beats. Who invented it falls to the wayside. I mean, Dave Lombardo is probably my favorite drummer, and Lars [Ulrich] of course, come on. I just love drummers that play to the music — and I think Lombardo does that really well while also playing a ton of shit over it and being himself.

GILBERT: I’m glad that you said that because that’s 100% been my MO. I’m not a super technical drummer personally. I’m no Travis Barker, but I could do a couple of fun things here and there. I just want it to be as straightforward, but also it makes sense, and it complements everything else that’s going on.

I’ve been listening to your band since I was maybe 8 or 9 years old. I’m only 27, so I’m relatively young, but I think I heard “Dead on Arrival” for the first time on Rock Band in 2006. I might have heard something off Cork Tree prior to that, but [that was] the first time I ever was like, “Oh, I’ve never heard of this band before.” I mean, at the time I was only listening to AC/DC, Guns N’ Roses, and Metallica — anything that my mom showed me — so I just felt something. It was something new and fresh to me, and it’s just stuck with me all this time.

Take This to Your Grave is still one of my favorite albums of all time. I didn’t get to see you back then, unfortunately, because I was young, and I didn’t even know really concerts happened when I was a kid. I remember I saw people wear tour T-shirts, but I had no concept of like, “Oh, I can go to that.” I saw you for the first time when you came back in 2013 at the Fox Theater in Oakland, and that was a life-changing event for me, for real. I still remember how you guys started the set with the curtain, and you opened with “Thriller,” and the curtain drops. It was a lot of fun, but shit. Obviously, you talked about Dave and Lars, two of the most influential drummers of all time. [Are there] any other hardcore bands that you specifically felt like you took influence from back then?

HURLEY: Sammy [Siegler] from Gorilla Biscuits and Youth of Today and all that shit. He’s an amazing drummer and is still playing in a hundred bands.

GILBERT: He’s still the drummer’s drummer, all these years later.

HURLEY: Alan Cage from Quicksand. [He] just played with Refused, and he was such an influential drummer to me because he is one of those drummers who plays to the music, but he just writes these really interesting… I mean, you could call ’em simple parts, but they’re not because most drummers wouldn’t even think of it. Chuck Biscuits from Danzig. My favorite fill of all time is in “Mother.” It’s the simplest fill, but I would never write that in my life. It’s too difficult to write.

GILBERT: Inherently, you want to think of something, and it’s like, “Oh, I got to do something that’s really complicated and memorable and really cool.” Now he’s just going to hit it. I’ve talked about Chuck Biscuits with my crew quite a bit. I mean, we’re all also big Joey C fans, and obviously Joey C fills those shoes properly.

HURLEY: Yeah, very much.

GILBERT: I saw [Quicksand] last year at Punk Rock Bowling, and it was fucking awesome. That and Rival Schools are definitely my favorite Walter [Schreifels] bands. I love Youth of Today, and that’s a Sammy band. I love GB, and it’s a Sammy band. I love all those bands, but he knows how to write a hook.

HURLEY: Yeah, he definitely does. I’ve heard a lot of people say that, but Sam was first for me, but Rival Schools is right next to him, so I just follow anything he does, really.

GILBERT: Everything he touches is gold. GB is one of my favorite hardcore bands of all time. I religiously follow what that band does. Funny enough, I’ve recently become friends with Charlie [Garriga] from GB and Judge and all them, the nicest man.

HURLEY: I have one more to add: Dennis Merrick. Earth Crisis is in my top favorite bands, influential-wise and everything, and Dennis is another drummer who just writes really cool parts.

GILBERT: He understands the memo, he received the memo, he read it to a T, and he’s like, “Cool, I know exactly what I’m going to do,” and everyone in the room’s going to be moshing, and it’s going to be perfect. I mean, Earth Crisis, I haven’t had the opportunity to see them yet because every single time they’ve come back here in recent years, I’m on tour. Unfortunately, I think I’m going to miss them again when they do that run with Judge and Integrity, which I was looking forward to because every single time any of those bands are here, I never get to see them. The last time Judge came to the Bay Area was with Down to Nothing, and it is funny: I backlined that show, so they played on my drum set, but I didn’t get to make it. What cymbals are you playing right now?

Michael Dubin

HURLEY: I just switched from DW to Tama and then switched to Zildjian in the last two-and-a-half years. Between MANIA and Stardust, during the pandemic, I just went down this crazy Lars path, with that white Imperialstar kit, like the ’88 to ’92. Tama and Zildjian were my first drums and cymbals as a kid, and the first music I fell in love with, that I wasn’t introduced to by my brothers and sisters, was the Big 4 thrash bands. I just wanted to play what they played. Most of ’em, like Dave, Charlie, and Lars, played Tama and Zildjian.

GILBERT: It just makes sense. I would go to Zildjian if I could. I don’t think they know I exist yet, unfortunately. Working on that.

HURLEY: I’ll tell ’em. What do you play now?

GILBERT: I’ve used every backline kit under the sun. I’ve used plenty of Yamahas, plenty of Pearls. There’s something about Tama. It feels and sounds better than most of the other kits I’ve used. I’m currently on Blackwood, which is a company that’s actually local to me. I’m using their aluminum kit. I was going for a maple stave at first just because I rented it out, and it sounded great, but I was convinced to get an aluminum, so here I am, and it’s awesome. Your snare, is that also Tama?

HURLEY: Right now it’s a Tempesta, which is a 14-by-7, but for a while I was playing an original bell brass from ’88 or so. I don’t know exactly when, but ’80s bell brass have this insanely thick rim. You know what I’m talking about? It’s super heavy, and it hurts to play at first because it’s so unforgiving. The vibrations don’t transfer — they just go right back into you, but it sounds insane, and I got that snare from Dave Elitch. Those are hard to find. But traveling to Europe or something, the rim cracked. So heartbreaking.

GILBERT: I’ve had my fair share of drum repairs in the past. I feel like no matter what, you can never truly repair. Do you use dampening at all on any of your drums?

HURLEY: I mean, it depends. Recording, but live, I prefer not to. I think once in a while my tech will throw a gel on the floor tom, if it’s too ringy. I like it a little more dead and just the low tone of it. But the rack I like to sing, and the snare, I like overtones because I think they get soaked up, and they just have a vibe to them that you can’t really tell unless it’s not there.

GILBERT: I can sit here and talk technical all day long, so I appreciate you humoring me. But I also wanted to talk about — obviously, I know you come from a very extreme world, be it Racetraitor or whatnot. Hopping into Fall Out Boy is a pretty jarring jump.

HURLEY: At the time, we just loved Green Day, New Found Glory, Saves the Day, and Lifetime. I was doing hardcore bands with Pete because Pete was in Racetraitor, and then he did Arma Angelus, which I played bass on for the first demo and drums with them live a couple of times. Patrick played drums for a couple shows, too. We were all coming from super political hardcore. At the time, the 2000s going into 2001, hardcore started to become more fashion-forward rather than political. The political side fell to the wayside, and we were all burnt out a little bit on it anyway. We just wanted to do something that was fun and less furious — just have a good time. I was in a band called Project Rocket with Kyle Johnson, who was in Misery Signals. I joined Fall Out Boy later, obviously. It was a no-brainer, and all our friends at the time accepted it. I think, at this point, people don’t really know where we came from, so it doesn’t seem like a big thing in terms of the audience.

It’s definitely informed us a lot in how we approach things and how we approach being a band. We all have equal share ownership in the band, and that’s the way we talk and discuss things, and how we still approach it. Coming from a really small, tight-knit scene informs a lot of how you do things. Jacob Bannon from Converge has a Substack, and I was reading his writing about the new Converge record. While they’re obviously super successful and everyone knows Converge — Jane Doe is one of the biggest hardcore records of all time — they still have to work other jobs to make ends meet.

He also talks about how digital music has affected record stores — a lot of the smaller independent record stores don’t exist anymore — and how that was such an important meeting place for people to discover music, which is how Joe and Patrick met and how he ended up joining Fall Out Boy. We found this dude who’s an amazing singer and songwriter, and it’s just sad that a lot of that stuff from that era just doesn’t exist in the same way. Obviously, it exists in different ways, and people still have community in different ways, which is one thing about hardcore that’s a through line that I love that might not exist in pop music. You can connect with scenes in different cities if you’re in a hardcore band. All of that has informed everything with us.

GILBERT: I couldn’t agree more. Where we are now as a band, we get to meet and play with other bands that don’t always necessarily come from the DIY and hardcore scenes. It’s kind of insane interacting with some people because we’re on such a different wavelength. It is like they’re living in a dog-eat-dog world, and for us, we’re like, “Hey, we can just help you out. It’s not a big deal! We’re all here together. There’s space for all.” It’s an ethos that I can see sustained throughout your band’s career all these years. I truly look at it as more of a mindset than anything, not just shows and music.

It doesn’t matter what scale it’s on. We just did the Movements tour, and the biggest show was in LA at the Torch. It was a 7,000-person show. But I truly don’t look at that any differently than I do with a headlining show we did in New Jersey for 200 people. Even if there were 20 people there, I would’ve looked at it exactly the same. We get these comments all the time now, they’re like, “Oh, it’s cool that you guys are doing these small shows,” and it’s not a small show. Two hundred people is still huge to me. The fact that that many people came out and saw us is still crazy to me.

HURLEY: Yeah, I see it the exact same way. For me, hardcore and punk built everything in my life. It’s how I met all my friends. It’s how I ended up in this band and every other band I’ve ever been in. We just did a festival in Monterey, Mexico, and a friend, Brad Clifford — who played in Since by Man way back and Poison the Well for a little bit — is a guitar tech, teching for Slipknot, Against Me!, and all these bands. Randomly, he was Patrick’s guitar tech, and I’ve known him since I was a kid from Milwaukee. All these connections have stayed with me this entire time throughout my life. Same thing with playing shows. It’s kept us all grounded. For me, doing Racetraitor and SECT shows, a lot of the shows we do are for 20 people, and I approach it the same way I approach the biggest show I’ve played. I give it my all. It’s super important to me, the fact that anyone’s there. Sometimes, I’ll have my kit, and the other bands don’t have a kit. They’re welcome to use my kit, and vice versa. We show up for weekend shows, and we all share everything.

GILBERT: The show must go on. Actually, I’ve seen both Racetraitor and SECT in those smaller situations. The first time I met you, very briefly in 2017, was when Racetraitor played Berkeley. Funny enough, very embarrassingly, we got to Berkeley at 2 p.m., super early, and we were literally windows down, full blast listening to Take This to Your Grave, and you happened to be sitting in front of the venue. We were like, “Fuck.”

HURLEY: That’s awesome.

GILBERT: I would assume you get your fill playing with SECT and Racetraitor, but I still, with what Scowl is doing now, get that itch sometimes where I’m like, “This is really cool. We just played to 3,000 people in a support slot, and they might not have known us, but we just won over the crowd. But God, what I wouldn’t give to be playing a hardcore show to 60 people right now.” It’s the weirdest feeling.

HURLEY: It definitely scratches that itch for me. A lot of it for me is the in-your-face political aspect to both bands. It’s important to me to still be doing that stuff.

What advice would you each give someone who’s just starting out as a drummer?

GILBERT: Just play what you love. As corny as it sounds, that’s how I got to where I am. Every time Scowl gets asked in interviews for any parting words, we always just say, “Do what you want. Who cares?” Life will go on no matter what happens. So play what you want, play what you love. It doesn’t matter if you’re good or not. I am not even close to being as good as some of my contemporaries, but I’m having fun. If you’re not doing what you love, then what’s the point?

HURLEY: That’s all I have to say as well. I think it was Damian Lillard who said, “Do it for the love. Don’t do it for the accolades or the money or what you get.” It was a story about people asking if he’s going to retire, and he is like, “Well, I still got it, and I feel I could still play until I’m 40. I show up, and I put in the work.” Whether it’s for a band or if you’re an athlete, whatever art form it is, if putting in the work is not fun and it’s not the reason you do it, the chances are, you’re not going to make it because it’s a hard world, and it’s a harder world than it ever has been. We’re in late-stage capitalism. The dollar may not be the reserve currency. America may be completely fucked, and we don’t know what’s happening with that yet, but it could potentially be really bad. Regardless of that, if you care about that kind of stuff or not, you’ve got to be doing something that you love, that gives you meaning, that brings you together with people you love. If you’re doing a band, do it with people you love playing music with, because you love it. If it takes off, great. If it doesn’t, you’re doing it. You love it, and that’s the reward.

GILBERT: You’re also a drummer. You picked the worst instrument you could have picked anyway, so you’d better love it.