Lauren Auder appears in our Fall 2023 Issue with cover stars Scowl, Yves Tumor, Poppy, and Good Charlotte. Head to the AP Shop to grab a copy.

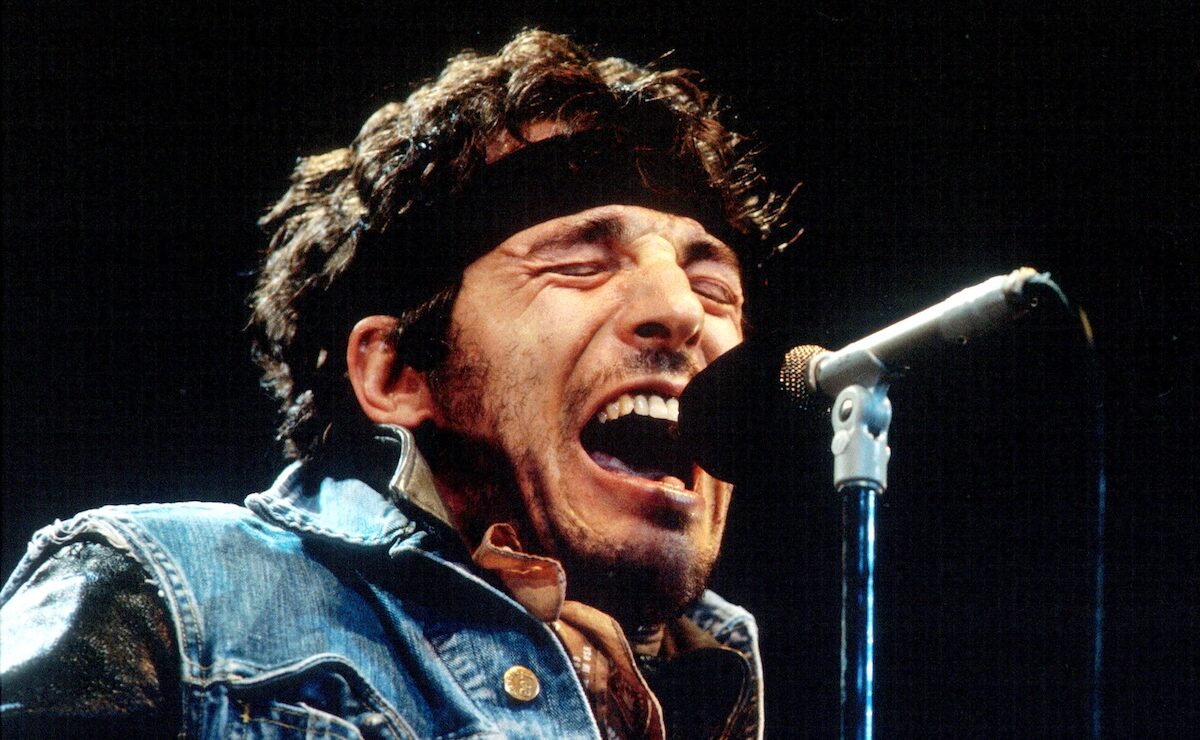

For the past 10 years, London-based French singer Lauren Auder has been treading in the soulful, orchestral swells of baroque pop. But with the release of her debut album, the infinite spine, her brooding baritone is chasing violence in the depths of darker, rougher waters.

Born in England to music journalist parents and raised in the French town of Albi, built around the Gothic Cathedral of Saint Cecilia, Auder was entrenched in the sounds and visuals of someone else’s creations. Imposing brick, religious imagery, and ubiquitous music from a prior generation — metal, folk, and alt-rock from the ’70s and ’80s — it wasn’t until logging online that Auder was able to explore on her own and see what worlds called to her most.

Read more: 10 essential My Chemical Romance songs that encapsulate every era

First, it was the emotional confessionalism of early aughts emo bands like My Chemical Romance. Then, it was the niche community of the DIY SoundCloud rap scene. Later, it became ambient and experimental music that echoed from the scores of her favorite movies. Like collecting scraps of textured fabric, the young musician began to sew a tapestry that felt unique to her, using pieces of the ornate baroque sensibilities of her hometown, the alt-rock comfort of her parents, the gnashing angst of her teenage emo obsession, and the haunting uncertainty of avant-garde composition.

Now, as a Celine darling and London scenester, Auder’s aesthetic can be felt in everything she touches. In the refined, bare-faced look of her appearance, in two spellbinding orchestral EPs, and in the gothic mark she’s made on indie-pop. But the infinite spine is a departure from what we thought we knew about Auder. With a project that was 10 years in the making, she knew she wanted to create something “more physical and visceral” than works past. And rock looks good on her. The incendiary debut album sees Auder dive head-first into the thrashing, angry noise that she has been ignoring all these years. While it isn’t always an easy listen, it’s a ferociously cathartic one.

Since publicly coming out as a trans woman in 2019, there has been a defiant vitality in Auder’s work, the electric touch of a woman who is finally free. Her raucous deliverance is distinctly encapsulated in the Mura Masa-produced “the ripple,” a furious track with frenzied drums and rasping snares that scream into the abyss. With Auder’s unique ability to capture darkness, harness its intense beauty, and then let it go, she hopes it will teach her fans that the dark may not be all that heavy.

What music did you find as a teenager or grade schooler that felt just for you?

My first big love was finding emo music and alternative-rock music when I was 10 years old. That was the first thing that felt like it was really my taste. I was a huge, huge My Chemical Romance fan. After that, I delved more into rap music. In my teenage years, I got more involved with ambient and experimental music.

Your debut album, the infinite spine, was a long time coming. What does this album mean to you?

It’s the culmination of almost a decade of making music, which is insane. It feels like the entirety of what I have had to say up until this point. It’s everything that I’ve been exploring and experimenting with over the past few EPs.

There’s this rush of energy in “the ripple,” this kind of raw industrial sound that when compared to your two caves in EP, which had this airy and light instrumental quality, is quite ferocious. Where did this energy come from?

One of the driving ideas of this album was that I really wanted to make something that felt more physical and more visceral. There are moments that are orchestral like my previous works, but as a whole, the palette of this record is much more dynamic. Even on a more practical level, it felt like an exciting opportunity to think about what I wanted to play live after all this time, which was a big influence on wanting to make more of a rock album.

How did your collaboration with Mura Masa happen?

Just being around the music scene in London. I came in with a vague brief, and it came together very naturally. It was genuinely written and mostly produced in one afternoon. We realized very quickly we had a lot of similar reference points. It’s a very sweet collaboration.

You mention the word “visceral,” and certainly the album art is that. The cover art for “we2assume2many2roles” and “the ripple” are very disturbing. They’re both images of you curled up with these imposing figures standing around you. Can you tell me how this imagery relates to the project?

A lot of the work on this record is a reckoning. A reckoning with what it means to be part of society, what it means to be seen by others, and just by being seen, being judged. Specifically as a trans woman, but also as a public person — and more and more, everyone is a public person — it’s about all this feeling of an omnipresent eye that’s everywhere.

As a young artist, there comes an enormous expectation of how much you share your life online. Have you figured out a way to use social media and connect with your fans in a way that feels comfortable for you?

I’m still figuring it out. A big part of this is trying to find these middle grounds where you can feel self-defined without sacrificing part of your being.

Let’s explore the theme of darkness a little bit. How has darkness been used as a tool to help your perspective?

This record is about digging oneself up from darkness. For those of us who have a melancholic predisposition — and I think many people making music or who feel the drive to express something have that as their natural state — it’s about not identifying with it. Not finding that to be the driving force of your personality and perspective. Since I’ve been a child, that is my tendency. Darkness is always there. You can read the news, you can look inside or look outside, and it’s there. What really inspired this record was the idea of pulling oneself out of that.

There are these intense contradictions within the record, of light and dark, ferocity and tenderness, these aggressive hooks, and then pulling it back to something more stripped back. How have these contradictions served you, and is there a playfulness in all of this?

I wanted to make a record that was a reflection of my life. Life exists in all these huge parallels. There’s definitely a playfulness. The more time spent with the record, the more I inserted some little winks and nods. There’s a lot of referencing in the music that is also even playful to myself, like a wink at the things that have inspired me in the past or things that I find amusing. And also playing into the melodrama and being aware of it.

If there’s a feeling or a thought or some type of energy that you’d like your album to inspire in its listeners, what would that be?

I think it’s just about a feeling. I want it to be uplifting, and I want it to be a pipeline to seeing a way out of darkness. In moments of distress, being able to make a way out yourself. Let’s see if I’ve succeeded.