Alternative Press teamed up with Spiritual Cramp for exclusive vinyl of RUDE and a T-shirt, limited to 500. Head to the AP Shop to grab yours.

Punk rock saved my life. It’s a bumper sticker, a T-shirt, an eye roll. But it’s also the truth. At age 11, a mixtape fell into my lap — track one, it started off with Butthole Surfers’ “Creep in the Cellar,” hit the halfway mark on Descendents’ “Bikeage,” and finished strong on the Stooges’ “No Fun.” It was a thorough starter kit for a kid who’d just begun to reckon with their otherness. I became obsessed, and barely looked back — in record time, I had a new uniform: box-dyed hair and thigh-high Docs that made my feet bleed. The music channeled an emotional range I had long felt alone with, one that I definitely didn’t hear on Z100 — the artists looked damaged, tough, walking through their own world, where rejection was relished rather than shamed. Without the portal punk music had sucked me through, and the multitude of scenes and sounds it led to, who knows where I’d be — but it definitely wouldn’t be here. And I’m not alone in thinking that.

Read more: 10 punk bands you need to hear, according to Sheer Mag

Writers, listeners, artists, we’re all reckoning with the reality that art will change as long as its context does. Twenty years after having my 11-year-old mind blown by Black Flag, I’ve become jaded, and that unadulterated excitement is hard to find. We’re too often focused on declaring rock dead, and then debating its revival, on pulling “true” punk in for questioning, or negotiating with “nostalgia.” Today, consuming what I can of the unending amount of music at our fingertips, with all of the modern nuance and microgenres that’ve been added to the mix, I have far more opinions than I do feelings.

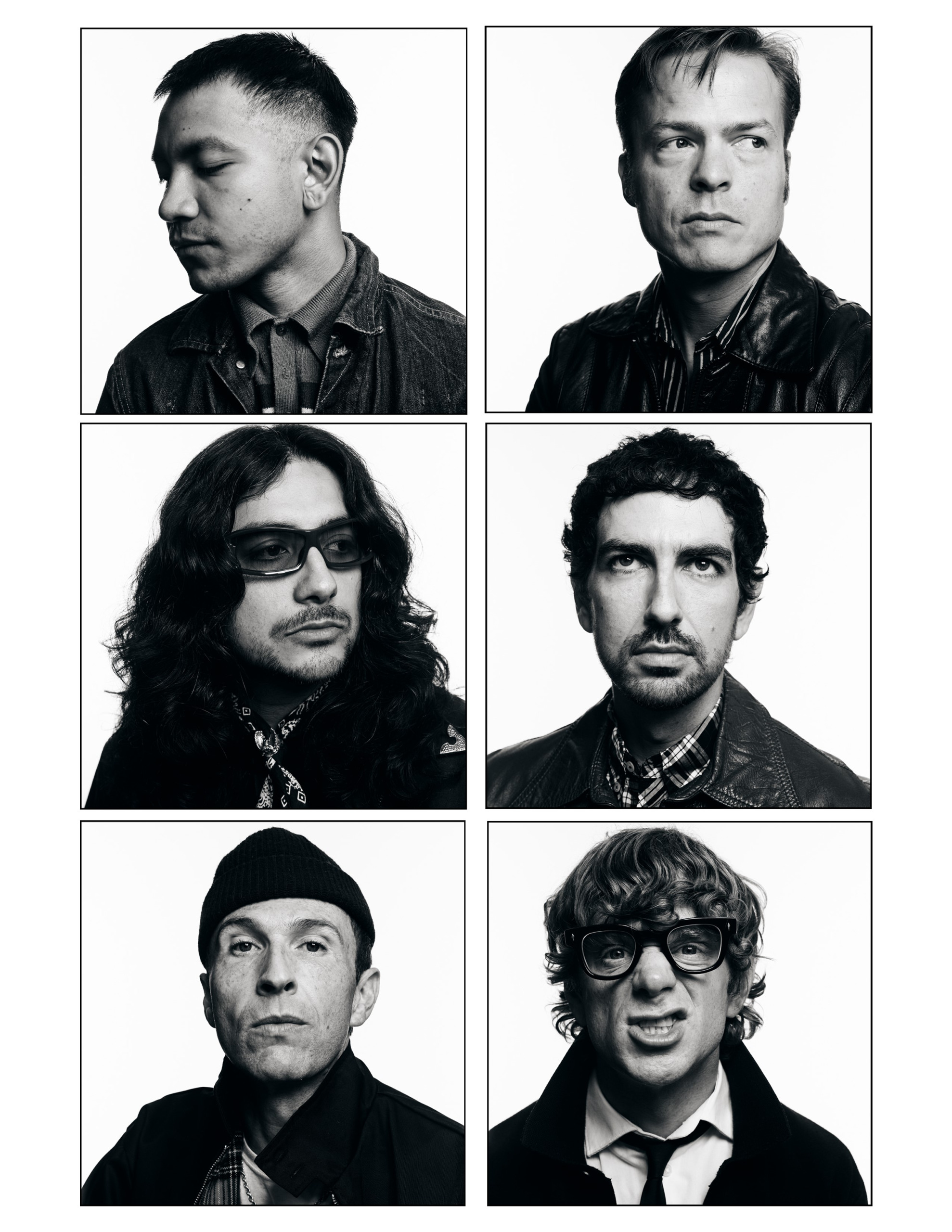

There’s nothing to debate about Spiritual Cramp. And from the first time I saw them, a rowdy group of six thrashing around onstage in penny loafers shouting “Oi!,” I felt something, and could tell that up there, they could too. It was fueling them, just like my mixtape had fueled me. These San Francisco natives serve as a salve — powered by white-hot energy and effortlessly cool swagger — fit to treat anyone hurting for pure, old-school punk rock and all it offers. True to form, this is big, emotive, and euphoric music, a drug for anyone unable to fit into a box, or who is in need of escape from the one they’re stuffed into. Theirs is a blend of brash dub, post-punk, reggae, and punchy Oi!, a sound, combined with their mod-inspired style, that draws from a different time — though it would be offensive to let a buzzword like nostalgia near this crew. Their unique recipe takes specific parts of each pummeling, angst-ridden element or reference, dresses them in Fred Perry, and blows the mixture up to pop scale. And they do this while preaching deeply vulnerable lyrics, speaking on struggles from anxieties and obsessions to the trials and tribulations of experiencing love. More so with each release, we’ve seen frontman Michael Bingham use the songs as a way to understand both himself and others.

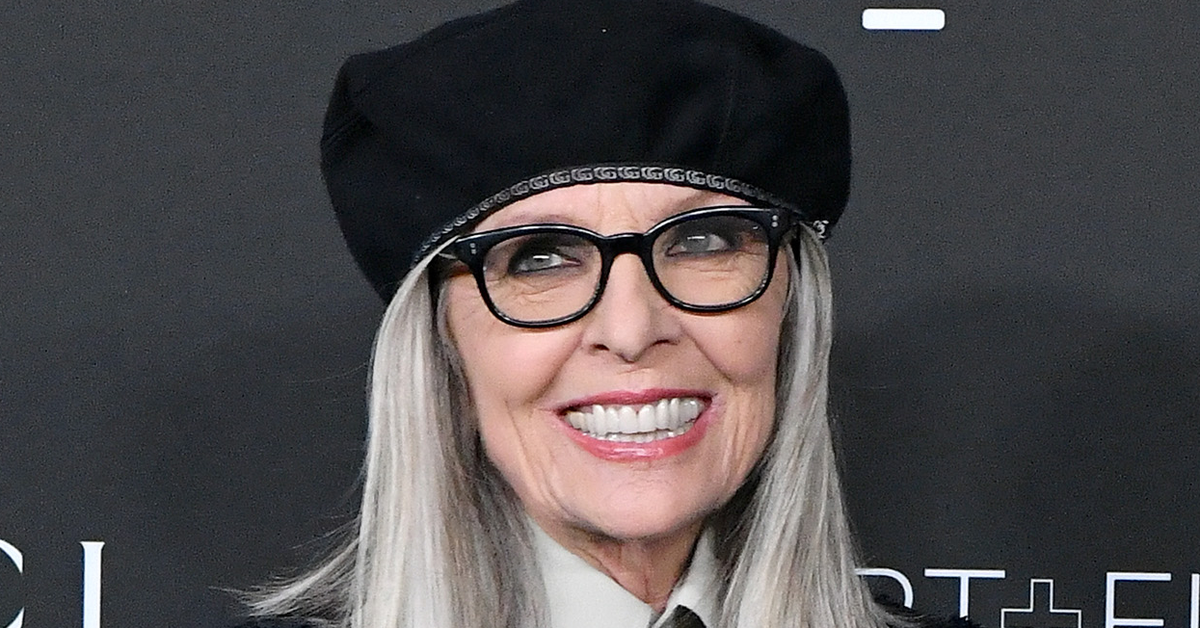

Daniel Prakopcyk

The band’s latest album, RUDE, burrows even deeper into Bingham’s mind and stretches the band’s sound beyond its previous limits. The secret, Bingham credits, is sitting through the discomfort of change. As a band built upon intentionality — in references, style, their especially stellar stage presence — after thorough work on himself, letting go was ironically the way to uphold that. They brought in a new producer, John Congleton. Where all previous albums had come together with Bingham and original member Mike Fenton in the writer’s room, for RUDE, all of the band members were a part of the process. And from each of those moves, the entire project, and group, grew. Side by side, Bingham’s trademark sense of self-deprecating humor and snarkiness sees RUDE unraveling his innermost fears — of leaving San Francisco, failure, the challenges he’s faced finding community in Los Angeles, and the daily reprieve of “keeping his side of the street clean.” It’s a far cry from his former ethos, “punk rock fuck you,” but it seems a happy medium can, and has, been found.

There’s a quote that I read by you, and I wanted to do a modern-day check-in about how you feel about it. “I am reflecting on what’s right in front of me. When we started Spiritual Cramp, what was in front of me was San Francisco. It was punching me in the face. I’m telling the story of six people who all go to bars and get drunk and fight and like the Sex Pistols and used to like stealing and doing drugs. That’s Spiritual Cramp’s story.”

Oh man, what a different story I am telling today. That’s so funny. That is definitely not what is right in front of us anymore, but it was when we started — and it was really fun. We were just being cool in San Francisco, partying and fighting and causing trouble. We were causing a lot of trouble. I’m going to date that… 2018. A lot has changed.

The question I have is — what came before that? What got you all there, doing that, as a group of people who’d connected over music? Then after, what happened? Let’s hear the prologue and epilogue to that “Spiritual Cramp story.”

That was probably within the first couple of years of the band. But I’d moved to San Francisco when I was 23, and I found my culture there. I moved there from a small town about 40 minutes north, and in SF, at the time, I felt much like I feel today living in Los Angeles — uncomfortable. It was a lot easier back then to feel uncomfortable because, at that point in time, I knew what to do. In 2018, I could just go party, and it would take feeling worried or fearful or insecure away. I found people who were seeking the same thing. So we started this band. A great therapist of mine once said, “You attract where you’re at.”

That’s where I was at. I was just looking to turn the light switch out, stumble around, have a good time, and be perceived. Spiritual Cramp was a great vessel for us to be perceived at the time. It was also the starting point of me learning how to be a thoughtful artist. Spiritual Cramp was the first band I think that I really ever did that I was very intentional with. I met Stewart [Kuhlo], and we started the band together with Mike [Fenton], who is still in the band. Stewart is no longer in the band, but we’re still very close. He would stop me and be like, “Hey, when we’re doing this band, what is your intention?” And I had never really thought about it. I just thought it was cool, wanted to put it out, and assumed everyone would digest it.

Let’s focus on San Francisco. Personally, I know that being a New Yorker has influenced my attitude, my affect, my aesthetic, everything I do. I am just curious to understand how other people’s culture and community and music scene have impacted them. What effects did coming up in San Francisco have on you, as a person and artist?

San Francisco at the time was very punk. Maximum RocknRoll is from San Francisco, which is something in the very DNA of everything that me and my friends were doing. So there was always this emphasis on being punk rock, and kind of laughing at other people who weren’t. All of our friends were in hardcore bands. Max [Wickham], who was another founding member of the band, lived at Maximum RocknRoll when we started the band. So that [scene] was definitely a part of the sonic and visual language of the band. It was like punk rock, fuck you, come see about it in person. I think it made us feel good to sit on a high horse a little. It’s hyperbole, but punk was like this thing that was supposed to be really elite. And it was at the time. But also at the time in San Francisco, with all these punk rockers, it was encouraged to be a knucklehead. Like, “Hey, let’s go out and get in fights.” It’s still like that there. People who I’m very close with, and people in our band who still live there hold that style down — and that style is a part of us.

There was hardcore punk at all these small venues like Thee Parkside, where we played our first shows, and The Hemlock — it was these hundred-cap rooms, and you would go and you’d get super drunk, and you’d play shows with all your friends. The lifestyle of San Francisco influenced us. You don’t own a car, you walk out of your house, you take the bus everywhere. It’s a late-night town, and that was influencing the fibers of the band’s inception. Then I moved to LA in June of 2021, and I was like a fish out of water. I was so uncomfortable, because here, it’s not cool to hold yourself down. It’s cool here to go as high as you can go, make something as big as you can make it, and turn it into a professional thing.

I was struggling with drugs and alcohol at the time. What happened was, in San Francisco, the party was great, and it continued. I made it a part of my personality. Then I moved here, and all these really cool people were sober. My drinking had started to eat up the other parts of my life. That ambition for music and the ambition for working hard and self-betterment, the part of my personality that I had designated to being a fun party guy got bigger and bigger — as I physically was getting bigger and bigger as well. I very quickly identified that most of the people who had what I wanted in Los Angeles were sober. So it was really easy for me to look at that and be like, “Well, that’s the next thing.” So I moved here, I stopped drinking, doing drugs, partying — and I was still spinning my wheels, wondering why what I was doing wasn’t skyrocketing into the sun or succeeding beyond my wildest dreams. I bring it back to that line, “You attract where you’re at.” My life had gotten so bad that I realized that I needed to take a shot at sobriety, to see if that was maybe the thing that was going to fix me. And actually, it wasn’t. What happens when you get sober, for anyone listening, is you get sober, and you are left with all the things that you were initially running from.

Have you heard the driving in the car analogy? Think of being on a road trip. You’re driving in a car, you’re accumulating trash, food wrappers, whatever. As you drive, you keep throwing it in the back. But when you hit the brakes — all that trash flies forward.

That’s kind of what happened. But for me, the cool thing about being sober when all that trash came forward, I looked around at it, and I said, “Oh, OK. Well, what do I do here?” I’m good at asking for help. I’ve always been good at placing myself around people who have what I want and then asking them questions. So I went into therapy, and I started working on myself, and I started taking care of that trash. It took three-and-a-half years. I’ve been in LA for four years now — and I’m finally at the place where I got up today, and I was like, “This is beautiful. I like this.” I spent four years being like, “I hate it here.” But I don’t hate it here. I’m just uncomfortable and afraid, and LA makes me feel small. And being able to admit that and talk about it is a lot harder than being like, “This place fucking sucks.”

As the work with myself progressed, the band naturally started growing. We got on a label that started helping us, and we got a great booking agent who is very smart, and we started working with a manager who really believed in me. As it shockingly started growing, those pieces started falling into place.

A lot of what this record is about is running back home. That is the safest thing in the world to me. I’ll go back to ’Frisco, fuck all you people in this fake town with my real homies. I got real homies back there who love me. It takes work to build a community of people who love you in a city that you’re not from.

I’m also curious what drew you to the lifestyle that you initially were a part of in San Francisco, with the fighting and the partying and the Maximum RocknRoll of it all?

The answer to that question goes back really far. I remember the first time I really heard music and connected with it. That was the first escape I ever had.

What was it?

It was AFI’s Black Sails in the Sunset. Then I heard Bad Religion. I was so angry. I had the worst home life, and I was so convinced that everyone around me was wrong. Then I heard this music, and I saw these people, and I thought, “There are other people out there who are embodying the way that I feel.” I became obsessed with that. I got a guitar, and I realized that was another escape. When you’re a kid at home and you don’t have much of a family or a support system, you have to find an identity somehow — and I found that in music. So I said, “I’m a punk, and I don’t like the police, and I don’t like religion, and the system is wrong.” That is what took me to San Francisco. You meet different groups of people in music, and you learn different things from them. And that’s the next part — you learn how to be that positive or negative, because you just want to keep that identity. But is that an identity anymore, or is that just an interest? Are you just taking influence from people?

When I moved to LA and got sober, I was left looking at myself, truly, without any makeup, in the mirror. My identity was taken from me. I was no longer this cool guy at the bar. I was just like Mike, who had an issue with drinking. When you get to that point, you’re like, “Who am I really?” Sobriety is something that has forced me to discover who I am.

The idea of identity versus interest is super interesting. I think I had a similar trajectory — broken home, saved by punk rock. I was completely obsessed. I wrote a fifth-grade school paper on the Sex Pistols and punks. But it inevitably transitioned into the same thing you experienced — developing characteristics of people that I found who were close to that, or at least people who looked really tough. I aligned myself with them, and it made me feel like I had thicker skin. So when I got sober myself, I felt totally like a newborn. I didn’t know what I liked. I didn’t know what I cared about. I didn’t know what I was interested in. I couldn’t listen to music when I first got sober. But as I did more work on myself, I was able to come back around, and it turns out I’m more like my fifth-grade self than I am any other iteration throughout my life. And those interests feel authentic to me, rather than authentic to others.

Literally, same. Another escape I found was perception. I love to be perceived. I love to be seen. I thought for a long time that if I can just increase my ability to be seen and perceived and continue to rely on these means of escapism like music and playing shows and being well-regarded, then that will complete me. And that is what my driver was for a long time. I got to a place — specifically right now — that is way further along in my wildest dreams than I could have ever imagined. And even though that happened, I was like, “Shit, I still feel the same.”

That’s the moment where you’re like, “OK, well, who am I? I’m deeply empathetic. You said the songs are really heavy, but also funny and cheeky. That is kind of who I am. I’m also a really emotional person, and I cry a lot — which is neither here nor there — and that’s not a part of the persona.

I did this in service of other people for a long time. I thought that it would help me. And I realized that that didn’t help. So a few months back, I reached this impasse in my life where we were in Europe, and we were playing to 7,000 people at this festival, and I walked offstage, and I felt deeply unhappy and sad. I went back to therapy twice a week. I’ve been going to therapy twice a week for two months. I realized I was lacking meaning — because the meaning that I was searching for I did find, and it didn’t fix it. I had to find new meaning. And the new meaning that I have recently found is that the only person I can do this in service of is myself. What does the 13-year-old version of me who is listening to Black Sails in the Sunset think of the fact that I’m on the cover of Alternative Press? It’s like, “OK, well then I’m doing it for you, man.”

You quit playing God.

I don’t think I was ready to take the mask off and be my full self at the time, and that’s OK. But now that I am, again, shocker, I’m seeing more success with it. So it’s like, “Fuck all of you.” This is the real fuck you.

Coming around to the new album, RUDE, let’s talk about it. You said everything is intentional, so I’m wondering: Do you begin the process knowing what you want to do, or does it unfold?

No, it unfolds where I’m at as a human being. When I’m writing lyrics and creating motifs for our records, it’s just an authentic representation of who I am and where I’m at. San Francisco is my safest place. Here in Los Angeles, you don’t know what anyone thinks of you. There are some scary people here. On the song “Go Back Home,” I say, “I don’t want to go back home.” I know deep down why I want to go home, and it’s because I’m afraid. I can’t make that decision. That’s not what the younger version of myself wants. So it’s like, “All right, well, I don’t want to go home, either.” But a lot of these songs were written in San Francisco, where I was walking around, staying above our friends’ venue Kilowatt. We did a bunch of writing sessions there. I was walking around the city, and while I was writing these songs, I was texting my wife, Barb, saying, “Babe, it is so beautiful here. We have got to move back!” And the reason is, it’s just so easy for me. I walk into all the coffee shops there, and I know all the people.

There’s this old song I wrote, and it’s called “Northern Soul Search,” and it’s on the Television 12-inch. The lyrics are, “Walking cool on Mission Street/You got the sponsored shoes on your feet.” I spent so much time making fun of people who would leave San Francisco and then come back, because it’s a thing that happens. People leave SF, they move to LA, and then they come back, and they’re like, “Yeah, what’s up? It’s me. I’m on the cover of the magazine.” It’s so easy to take shots at people like that. Ironically, when I’m walking around the city and we’re writing this record, I’m like, “Man, this is my place.” But at the same time, I don’t know if I’m growing there.

When I work out all the time and am taking really good care of myself, I’m super uncomfortable. But what happens is after six months of working out every day when you don’t want to is people will be like, “Hey, man, looking good.” And you’re like, “Oh, that’s crazy.” It’s because I’ve been uncomfortable for six months. Again, what does the young version of myself want me to be?

I know that there was a shift in the way that you are writing as a band on this album — you all worked together more collaboratively. With an album that is so personal, how is it working with other people to craft these songs? It sounds like we do have a lot in common. For me, that would be extremely difficult. But I also am a very competitive and isolated person.

I’m as well. But again, in the spirit of growth, I am able to be the kind of person who can recognize what I’m now. Now I say this with a lot of humility, but I can be the kind of person who can assess what I’m doing and be like, “Shit, I need help.” For that first record, it was a good record, and it felt like it was received pretty well. It did good for where the band was at, but I knew I needed help with writing. I wrote all of the music with Mike, our bass player, and we did all of the guitars. Jacob, who was in the band at the time, recorded a lot of the guitars, but it was with me sitting over him and then being, “Play it this way, play it this way.” Jake is just an angel and always, so he would tolerate me, too. But at the time, that was all I had. All I had was the ability to do everything completely myself. I saw where that got me with the first record, and that was cool. I thought, “Well, I’d like to grow more than this because we are taking this band very seriously, and I think we might need some better songs.” When we started writing the record, we had been this incarnation of the band for a good two years on the road. So Nate, Julian, Orville, and Jose, these guys got to know me really well, and there was a real trust that was created. And the flip side of that is I got to know them really well, and I trust them. I believe that they understood exactly what we needed to do, and they had bigger and better ideas for these. Our band has a sonic and a visual language.

Yeah. It’s very specific.

These guys are really good at hearing what I’m saying, and we all have the same interests. When it came time to start writing the record, I knew I needed help. I knew I had these really, really smart and capable producers and guitar players and musicians who had spent two years ingraining themselves in what we were doing. Then we went and worked with John Congleton, who was a producer, and John spoke a lot of the same language as well. He was bringing up bands like the Stranglers when we worked together. He knew our references. So between the guys and their beautiful ideas for what we were doing, and John, it was able to harmoniously come together, and there were some growing pains, obviously.

That sonic and visual language you mentioned — I’d love to hear you articulate what that is. How would you describe Spiritual Cramp to someone who hadn’t heard it?

I think we’re just an indie-rock band with punk influence and dub influence. Some people hear the English Beat. It’s funny to me: Sometimes people will be like, “Man, they’re like a dub band.” The thing is, though, whatever people hear is the fabric of our DNA. The English Beat is a band we use a lot in inspiration, a lot of us onstage. We’re also like a ska band in a way because there’s so many people onstage, but then you watch it live, and people are like, “No, they’re ‘hardcore-adjacent’ because we’re so ferocious live.” Those are the things that interest me. Jangle pop, mod music, C86 comps, oi music and punk rock, ska, reggae, and indie music, Arctic Monkeys. These are all the things that form what we’re doing — with a heavy emphasis on looking cool.

In the past, you said that Spiritual Cramp exist at the intersection of who you are and who you want to be. When you think about RUDE, where does this fall on the spectrum of autobiographical to aspirational?

RUDE is autobiographical. I have almost lost the aspirational part of the band. Except in the style, and clothing, something that I talk a lot about. As a human being on Earth, I want to have a visual identity when I walk in a room. So I can speak without speaking, you can do that through style. I just think that the way that we present ourselves is a way of saying, I want to be mod. I want to be a punk rocker. I want to be an indie rocker. We do put a lot of thoughtfulness into how we are perceived still, in a way, because it’s about who we are and what we like and what we think is cool. I guess you can’t escape the intersection of who you are and who you want to be, but you can present it as authentically as possible.

You have torn with some pretty iconic people. I mean, Iggy Pop, that’s fucking crazy. The Hives, Rise Against, Bad Nerves, and L.S. Dunes. And since this has been such a growth process for you, what would you say that you’ve learned from your experiences touring with other artists?

Sometimes I think that we put too much emphasis into planning things like our stage show or our outfits or banter, because that’s what you’re talking about is the live space or how to move. And sometimes I’ll be like, “Man, are we just too thoughtful?” Because a lot of people like to be nonchalant, right? Then you meet the biggest, most successful ones, and they are not accidentally doing what they’re doing. It’s empowering. We have looked up to some of these artists for so many years, and now we get to go on tour with them and see them every day and share buses with them. You can really tell that thoughtfulness as an artist is the most important thing. When you go on tour with some of these people, you’re like, “Oh, this is all a piece of the art to you, and you can never stop getting better.

What has happened is Spiritual Cramp has gotten access to some of the largest rock bands out there. And what you find is they are doing the same things we are, and they’re super cool. These bands that we have gotten to play with or that have shown us support, they’re very humble and cool, and they don’t have a cool guy persona. They’re like, “Hey, what’s up? I love the last record. Thanks for coming on tour. You guys are great”. It’s a reminder: I need to be more humble, and I need to be kinder to people who can’t help me — because I can’t help the Hives. I can’t help Pele Oquist, but they’re helping me by taking my band on tour. Or Rise Against or Iggy Pop or any of these people. All they’re doing is just throwing us a bone because they see something that they think might be a little cool.

This is all true. But I wouldn’t say they’re not helped by you in some ways. Some of those people have been inspired or influenced by you guys, too — after that Rise Against tour, L.S. Dunes are so stoked on Spiritual Cramp. They ride for you all.

We ride for them, too. It’s so cool to get to meet these people. Those guys are all in famous bands. I saw Coheed and Cambria posted a photo of Travis [Stever] in one of their stories the other day, and he was wearing a Spiritual Cramp shirt. Frank [Iero]’s band just sold out the biggest stadiums in the world, so to not only get to meet him, but to figure out that he, as a successful artist, embodies the things that I also think are deep down cool — which is just being kind to people — you’re like, “Dude, I’m on your team forever.”

It goes back to our initial conversation, about finding meaning, purpose, and leading a value-driven life — and how that’s the key to longevity and success. Even when it relates to fame and finance, or the public and social media, there are still ways to align with your values. It’s really noticeable when people do that.

When I start working with artists, one of the first things I usually ask ’em is what do you want to be — do you want to be a famous person? Do you want to be a celebrity? Because you have to define what it is that you want for yourself as an artist. Do I want to be Bono? Is that what I’m here for? I’m not. I’m here to just be in a certain space in a certain way. It’s a personal question, but this is all about finding your goals as an artist and then moving towards them, and doing that with meaning. It’s goal-based decision making, which is another thing I talk about a lot. All of my decisions are based on goals. I’m not just like, “That doesn’t feel right.” No. Does that serve the purpose of me being an artist who wants to exist in this space I want to exist in?

The last thing I wanted to touch on is the tour you’re going on next year, presented by AP.

Yeah, very excited. It’s our first full U.S. headline tour. I think it’s going to be a really good tour. We’re having some exciting conversations about bands that will be on the tour. We have done so much touring with other bands on their tours. They have picked our band to be a part of their tours, what they wanted to curate. So this tour for us is the first time in 400-700-cap rooms that we get to curate what we think is cool. It’s so exciting to finally be like, “All right, you know what? This is who we’re going to bring, and this is who we are excited to show our fans,” because so many awesome artists have done that for us. We’re being very thoughtful, and the fact that AP is presenting the tour is amazing.

People are going to love it.

I hope. I mean, all you can do is set the dinner table and be like, “Hey, this is what I cooked.”