[In a life full of quirky projects, David Lynch’s comic strip “The Angriest Dog in the World” still stands out. Similar to Dinosaur comics, a single strip, drawn by Lynch, provided a palette for a weekly dose of philosophy and weirdness, running from 1983-1992, when Lynch must have become too busy to continue. The strip ran in the LA Reader overlapping some of Lynch’s rise to tremendous fame, alongside Matt Groening’s Life in hell and Lynda Barry’s Earnie Pook’s Comeek. Truly the golden age of alternative comic strips.

With all the attention to and tributes to Lynch’s work after his death, I was lucky to run across (on FB) this account of working on “The Angriest Dog in the World” from Dan Barton, who was editor at the Reader back in the day. Shared with Barton’s permission, yet more proof of the wonder that was David Lynch the man and creator. – -Heidi MacDonald]

By Dan Barton

Back in the eighties, I was the editor of an alternative newspaper published here in Southern California, the Los Angeles Reader. I was young, inexperienced, and in over my head more than just a little bit. On a miniscule budget I dealt with mega talents on a daily basis. Some who went on to greater glory, some did not. More on that another time.

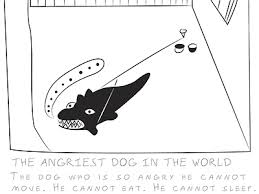

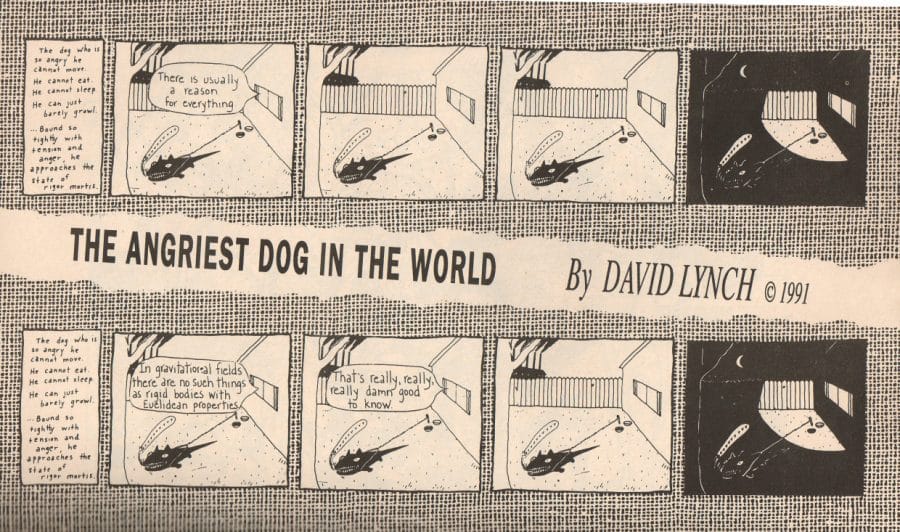

One of the regular features in the Reader was a comic strip called “The Angriest Dog in the World” by . It was comprised of four panels, hand-drawn by Lynch at one time. It featured a growling dog tethered outside a home, with his owner unseen except for captions that drifted out a window.

Lynch had submitted the art a few years before I arrived. Every week he called in the captions by telephone. They varied each strip, but the art stayed the same. (This was pre-fax, pre-email, pre-office computer.)

I’ve heard from a former Reader staffer about how Lynch would call in every week from the set of “Dune,” the phone service in Mexico making the calls filled with static.

“The Dog,” as we called the strip around the office, was another feature of the Reader that was part of its perpetual quirkiness: something that would only exist in that particular publication.

The intercom on my desk would buzz, and the receptionist would say: “It’s David Lynch” as if the pizza had just arrived for lunch. I would pick up the phone and we would exchange pleasantries and then he would say “I got another Dog for you.” I’d write down the captions and then he’d sign off. Our conversations weren’t very long—at first.

Sometimes we chatted about his films. That was how I first saw his version of Dune. I rented it (on VHS, believe it or not), watched it at home in my apartment in Santa Monica, and then talked to him about it the next time he called. He was not one to dwell on the past; he was busy making another film on the East Coast. But . . . he expressed regret that the special effects didn’t quite convey what he was going for. I once asked him what the noxious black liquid was that Kenneth McMillan as Baron Harkonnen doused himself with in the midst of a (literally) flying killing rage. His reply was simple in his particularly lilting way of speaking: “I don’t know,” he said, “but it does something to him, doesn’t it?”

At one point, someone in upper management suggested Lynch not get paid for doing the strip. “See if he’ll do it for free,” I was told. Lynch was paid a pittance: a mere twenty-five dollars a week. For some reason, this was made this a particular point of contention.

When I ran this by Lynch, he chuckled. “No,” he said. “You pay for it. It isn’t free.” I remember management’s disappointment on hearing this. I was blamed. I hadn’t asked Lynch right.

The high point of my phone calls with Lynch came when he invited me to a screening. He had told me he was in town working on his latest film: editing, scoring, all the duties of post-production. Then, one day he asked if I wanted to see it. I said of course. The next week, an assistant called back with a date and time for a screening. When he called in that week’s strip I asked if he was going to be there. We had never met in person. He said no, but he wanted to know what I thought of the film after I saw it.

The screening was at the De Laurentiis Entertainment Group Studios. I remember the screening room was not even half full. There were statues of a gold lion on both sides of the screen. A gold lion was the icon of the company. I think the screening room was on Sunset Boulevard, but I am not sure.

I brought a date. The lights went dim, and the movie unspooled.

The film was “Blue Velvet.”

I saw it months before it was released, before anyone knew anything about it. Now I realized I must have been one of the first people in the media, possibly the country to see it in its finished form.

It was a mysterious, magical movie experience, one I will never forget. Later that week when David called in to give me the captions for that week’s strip, I raved about it to him with genuine enthusiasm. In his David Lynch way, he received each of these gushing compliments with a simple graceful “Thank you.” When I asked him what the mysterious gas was that Dennis Hopper inhaled from a canister through a mask that sent him into a violent temper, he gave me the same reply I’d heard before: “I don’t know,” he said, “but it does something to him, doesn’t it?”

I left the Reader later that year for a very simple reason; I had sold my first novel. I received an advance based on an outline and sample chapters. It was enough to live out at the beach and write to my heart’s content for at least six months.

I remember my last phone call with David. I told him what had happened and he perked up at the news. “Oh,” he said. “You have to go do that.” Then in farewell, he said: “Good working with you.”

I ran into him one more time, in a supermarket in Westwood. He was with Isabella Rossellini, who had been so memorable in “Blue Velvet.” I approached him and introduced myself. He smiled and said it was good to meet me in person. In farewell he grinned, winked, and said, “Good luck to you, Dan.”

I never saw or spoke to him again. I remember a few years after I left the Reader when the country’s biggest TV obsession was “Twin Peaks,” a show that gripped the viewing public’s imagination with its unwinding plot, stunning visuals, and offbeat characters.

I guess those are the lessons I learned from talking to David Lynch: Never write for free. Do it the way you see it. Don’t be afraid to fail. You don’t need to have all the answers. Above all, work. Create. Get it out there.

So long, David Lynch.

The Angriest Dog in the World was brought to print in 2020 in a limited edition of 500. Otherwise, the strip exists only in yellowing scans and our memory, which is perhaps how it was meant to be.