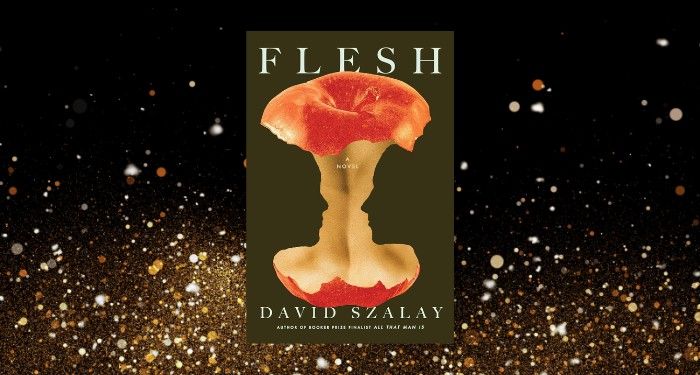

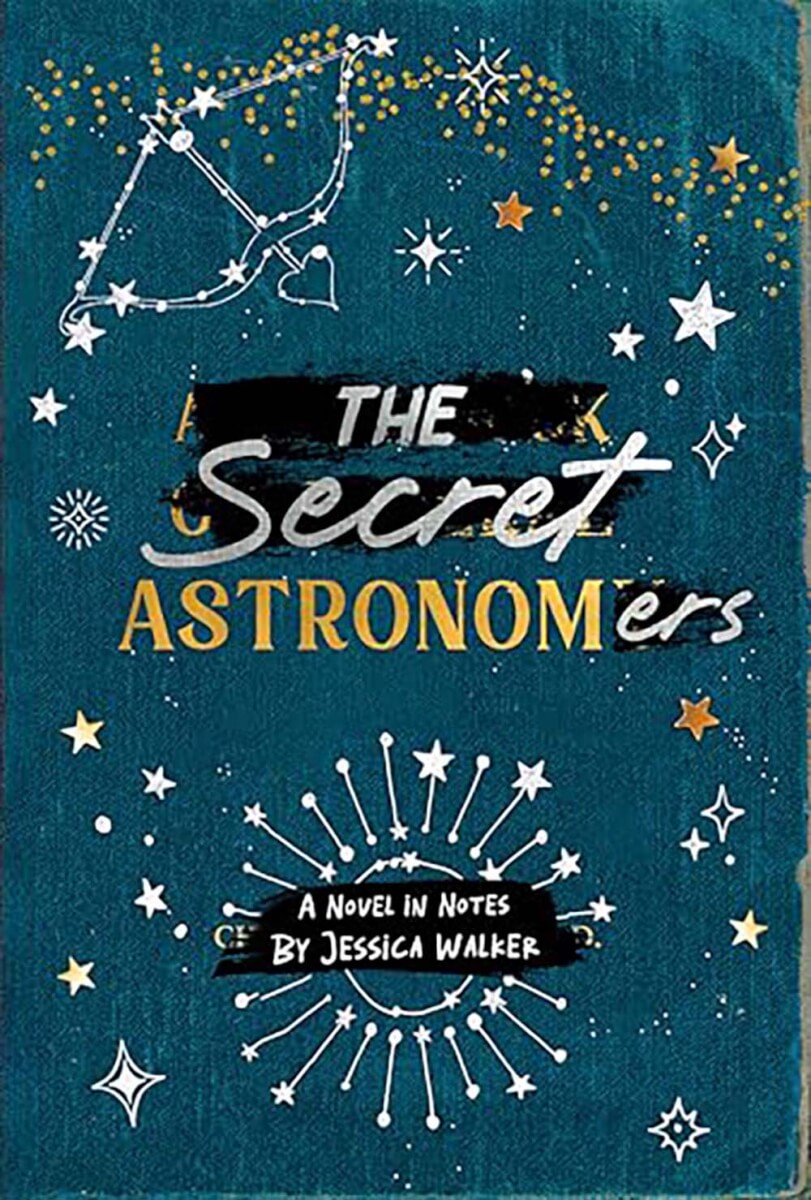

Before we look back at the history of National Book Awards winners and attempt to scry this year’s awards recipients in our crystal balls, let’s take a look at our 2023 finalists, announced by the National Book Foundation yesterday:

Now, if you claim membership to just about any bookish community, you’re sure to find someone who’s already added these books to their TBR. Books recognized by the National Book Awards (NBAs) breathe rarified air. An established, time-tested mechanism has deemed them Important. The message is: if these books weren’t already on your radar, they should be. The NBAs have been around for more than 70 years, so the Foundation must know something about finding these urgent and necessary reads, right?

According to the Foundation, the awards were established “to celebrate the best writing in America,” currently selecting winners in the categories of Fiction, Nonfiction, Poetry, Translated Literature, and Young People’s Literature. While I’m not always compelled to read award-winning books, I do pay attention to some of the big literary awards, including the NBAs. Reading is such a subjective experience, and I’ve read some award-winning snoozers in my time, but there’s something to be learned by observing which books float to the top of distinguished and buzzy lists of all sorts. Some of the lessons are frustrating, and some of them might hold interesting information about the zeitgeist.

Who They Are Now vs. Who They Were Then

The Foundation lists their core beliefs as follows:

Books are essential to a thriving cultural landscape

Books and literature provide a depth of engagement that helps to protect, stimulate, and promote discourse

Books and literature are for everyone, everywhere

This is what’s posted on their site today, but if you look at the winners of the very first NBAs in 1950, you might be led to believe their core beliefs had more to do with recognizing white men writing on the American condition:

I expected to find, if not this specific list, something similar to it. To be more direct, I didn’t expect to find a Black or Brown face amongst the inaugural winners, knowing they were awarded in 1950—the dawn of that era certain people like to idealize because the country unapologetically rallied around white masculinity. I can’t say for certain, but I’d wager that nobody at the Foundation was concerned about the homogeneity of this list when it was decided.

I say this to say it was ultimately the question of who was telling these Important stories that contributed to urgent national discussions that dogged me as I perused the archive of winners. What seems obvious today—that it’s not just about what’s being said of our lives and times but who’s doing the speaking that matters—wasn’t always a significant part of the conversation, if it was part of the convo at all. After reviewing the first winners, I found myself scanning the years to see when women and BIPOC authors appeared.

Click here to continue reading this free article via our subscription publication, The Deep Dive! Weekly staff-written articles are available free of charge, or you can sign up for a paid subscription to get additional content and access to community features.