EXCLUSIVE: “Peggy Ramsay used to say ‘agent’ is the most disgusting word in the English language,” ponders Adam Welsh, the founder of Divergent Talent Group (DTG).

For a group of changemakers making their way through the UK’s bustling agenting landscape, the words uttered by Ramsay, one of the greats — who repped the likes of Stephen Poliakoff, David Hare and J.B. Priestley — don’t exactly chime.

These agents are spearheading the UK TV and film industry’s drive to improve representation for disabled talent, a minority that makes up 20% of the British population and yet is vastly under-utilized both on the small screen and behind the camera.

Welsh founded his agency devoted to repping neurodivergent talent in 2021. Sara Johnson and Julie Fernandez have recently joined Casarotto Ramsay in an intriguing dual role representing, training and developing talent, while long-time advocate Andrew Roach, whose clients include Britain’s Got Talent winner Lost Voice Guy, was snapped up by Insanity last year. Plenty of others are making waves in the space as well, and some, like VisABLE People founder Louise Dyson, have been banging the drum for years.

And it is a drum that requires banging.

While broadcasters and producers have talked tough on improving disability representation since Help scribe Jack Thorne’s blistering 2021 Edinburgh MacTaggart address, the figures paint anything but a positive picture. Just 8.2% of UK TV acting and presenting roles were filled by disabled people according to the most recent data from diversity monitor Project Diamond, with this figure at a paltry 6.5% for behind-the-camera talent — both woefully shy of the national average. A broadcaster-wide target set in 2018 to double representation off screen within two years failed miserably and will take another seven to be achieved, according to recent research, which acts as a constant and damning indictment on progress.

Enter agents old and new, acting as gateways and clearing the path to better representation.

“Agents for change”

“We are agents for change,” says Casarotto’s Johnson, a former studio drama exec and EP on Fox’s War of the Worlds and Deep State. “An agent’s lifeblood is advocating on behalf of their clients, but what has been missing for disabled talent has been people advocating appropriately within an industry that is still full of barriers and doesn’t have great facilities.”

She adds: “When you go to other countries, the piece of the puzzle missing is the agents. Who are they, who will create rate cards and who will make work secure and affordable? Now, we get to carry on and scale that.”

Johnson and Fernandez, the latter of whom played Brenda in The Office and is a fierce advocate, are focused for the most part on access co-ordinators — a role that has sprung up on productions in recent years and is crucial to helping disabled talent integrate on set. They heap praise on Casarotto MD Anna Higgs, who fought the pair’s corner and argued that knowhow developed across their years running disability consultancy Bridge06 could only be of benefit to the agency.

The pair are now supporting and representing dozens of access co-ordinators, who can be trained up and given work on productions, while they are also advising indies on access more generally. This comes more than a year after the launch of the UK broadcaster-backed TV Access Project, which was forged to improve the appalling accessibility issues that riddle the sector, with the aim of “no disabled talent feeling excluded by 2030.”

“The idea of being an agent for access is all about putting requirements in place so that people who are deaf, disabled or neurodivergent (DDN) can get on with being brilliant and not worry about how they hell they are going to get to the toilet,” says Fernandez. “As the process goes on, we will be looking at all Casarotto clients who are DDN, making sure they have access requirements met on all shows.”

For Johnson, “we are adding the A [for access] to D, E & I.”

It’s tough but necessary talk from the pair, who radiate positive energy and have big plans to expand their offering.

Roach, who joined Insanity last year as Senior Talent Manager with a roster of some of the UK’s biggest disabled stars, including presenter Samantha Renke and Under the Skin star Adam Pearson, believes “there has been a recognition that we all need to play our role in making change happen and educating ourselves as to the needs of disabled talent.”

“What I was doing was an anomaly for a long time and I often felt like I was shouting into a black hole,” says Roach.

In a similar vein to Casarotto, he says Insanity is taking a fresh approach to disability representation that “isn’t performative.” This attracted him to the role, along with “being given the opportunity to work for a larger company.”

Roach says things have “changed considerably” during his 10 years managing disabled talent, with more positive examples of representation and “conversations about what can be done as opposed to what can’t.”

Both Roach and Johnson are careful to pay tribute to those who laid the groundwork for this push. “We stand on the shoulders of giants,” says Johnson. “There are people who have been banging their head against these barriers for a long time and the joy of somewhere like Casarotto is recognizing there is now a commercial imperative, as well as a moral one, to do this better and be part of the move for change.”

One woman whose head must hurt after years of head-banging is VisABLE founder Dyson, whose agency turns 30 this year. She has had a front row seat to all the change over several decades.

Dyson has placed dozens of actors on some of the biggest British TV shows including Call the Midwife, Doctor Who and Hollyoaks, and she was awarded an MBE in 2016. She says VisABLE has been taking calls from Hollywood of late and recently landed a client a role on what will undoubtedly be one of the biggest movies of 2024, Dune 2, while others’ successes have included the likes of West End shows.

“Thirty years ago you wouldn’t see anyone in the media in any kind of advertising campaign, film or TV series with a disability unless they were faking it or, in the case of an advertising campaign, stretching their hand out to raise money for charity,” she tells Deadline. “It has been like turning around a super tanker. It was five years before we even got a booking.”

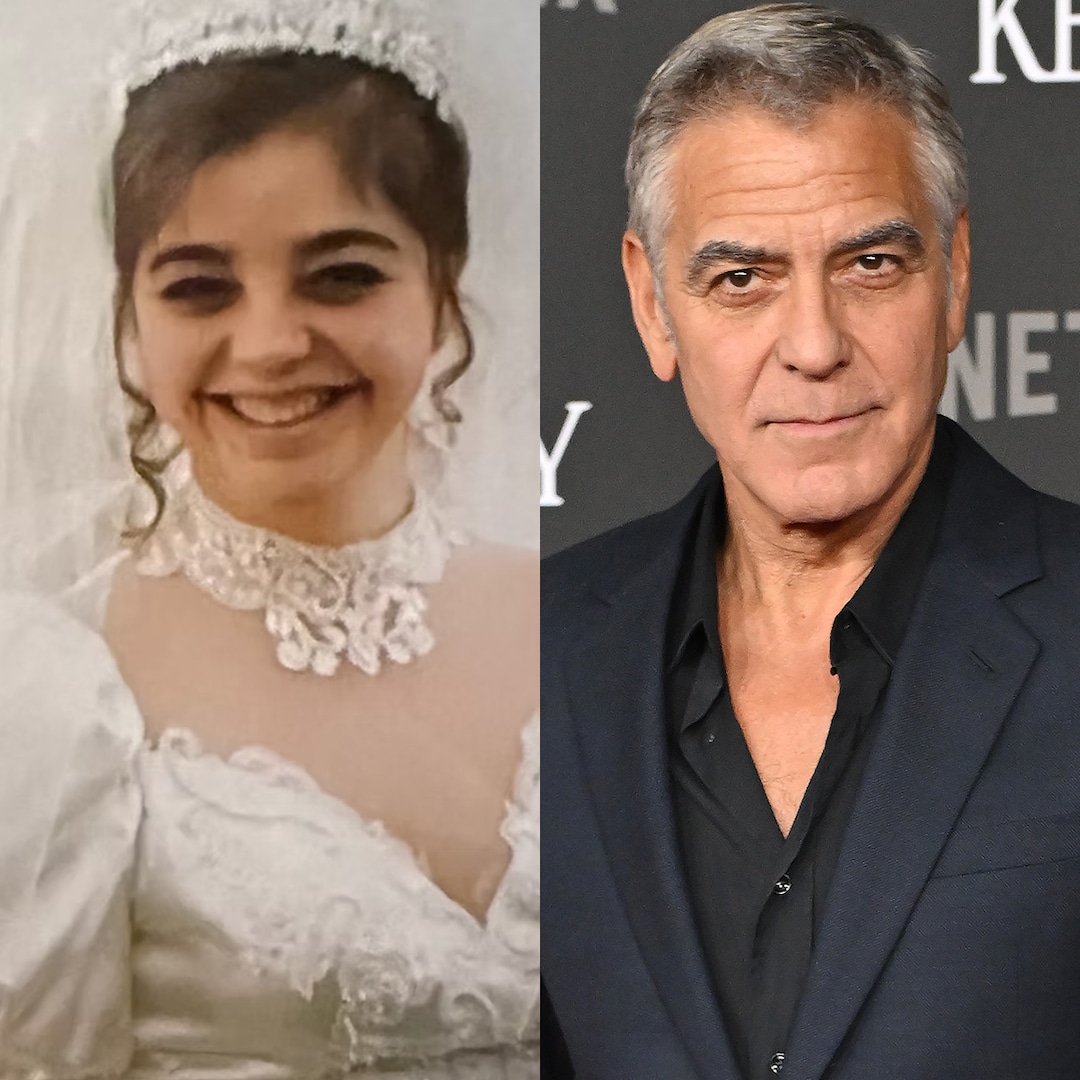

A turning point for Dyson came in the late noughties when she landed one of her clients, Cerrie Burnell, a job as the first ever disabled presenter on CBeebies. Burnell faced some unpleasantness, but became a shining beacon for young disabled children and has since flourished. “The BBC received 12 unpleasant responses from bigots saying that she was giving their kids nightmares, while there were in excess of 10,000 people saying, ‘This is fantastic,’” adds Dyson.

Incidental casting

Cerrie Burnell winning a BAFTA Children’s Award

Ricky Darko/BAFTA via Getty

Burnell was hired irrespective of her disability and this taught Dyson that the next stage was for clients to be placed in “roles where being disabled doesn’t matter,” rather than those that are “disability-specific.” “The vast majority tended to only think to cast a disabled actor when there was disability written into the role,” she says.

Another game-changing moment was United Agents client Liz Carr‘s casting as Clarissa Mullery in the BBC’s long-running forensic drama Silent Witness, Dyson adds. This catapulted Carr, who recently starred in This is Going to Hurt, Loki and The Witcher, to fame and acclaim. Equally notable was Ruth Madeley‘s casting in Russell T Davies’ futuristic BBC/HBO drama Years and Years, a role that wasn’t intended for a disabled actor but was rewritten to accommodate for the actress, who recently guest-starred in the Doctor Who 60th anniversary special and is represented by UTA-owned Curtis Brown.

BAFTA Chair Sara Putt, who runs her own agency, celebrates how “incidental” having a disability has become to certain roles, citing Lola Campbell’s character in BAFTA nominee Scrapper, who wears a hearing aid that in no way “defines her character, but normalizes it.”

But these roles are few and far between, Dyson says, and she worries the likes of Carr, Madeley and Campbell remain outliers, even as prestigious agents become more likely to take on disabled talent — a development she is agreeable to and often consults on to “dispel myths and fears.”

Putt has been spearheading a drive for improved representation in the TV industry via her agency, Sara Putt Associates, for a long time. The outfit runs trainee schemes intended to help those behind the camera navigate the cavernous paths of the sector. They are not intended solely for disabled talent, but are is attended by many from the disabled community.

“We started them because while the [under-represented] talent we were speaking with was incredibly technically creative, they were perhaps suffering from a lack of knowledge and understanding of skills such as finances, networking, relationship building and interview technique,” she says. “Many of my clients were moving from job to job in a way that was reactive rather than strategic.”

The push for a more joined-up approach has coincided with a greater degree of openness from disabled people to declare their conditions, one that Putt says is welcome, especially where neurodivergent people are concerned.

“A great number of our clients would now declare as being somewhere on the spectrum,” she says. “It goes back to the argument of why you’d need an access co-ordinator on a shoot where no one is declaring a disability. If that co-ordinator is there and safe spaces exist, then disabled people will be more willing to have those discussions.”

Divergent Talent Group (DTG)’s Welsh points out that there was a tendency for casting directors in the past to “tell clients to say they were not autistic or had ADHD, as they thought it might lose them the job.”

He points out that some of the industry’s biggest and best talent are neurodivergent, citing the openly-dyslexic Steven Spielberg and Steve McQueen, or Greta Gerwig, who was diagnosed with ADHD as an adult. Welsh understands all too well what Barbie auteur Gerwig would have gone through, having started his career as a multi-hyphenate who became disillusioned, “finding myself having intense periods of hyper focus on one thing, and then losing interest.”

“When I was an actor, I’d be up for ‘gross misconduct’ for messing about on stage and that was because of a condition I didn’t know I had at that point,” he says. “I had this meandering career. I was finding myself thinking about what I wanted my life to look like and being an artist wasn’t part of that anymore.”

It wasn’t until he was diagnosed with ADHD during the pandemic and simultaneously became a father that Welsh realized he could help others who had been in his position.

His agency dedicated to neurodivergent talent has been running for more than two years now and has flourished. Welsh says the response to “an idea I had in a sushi bar” has been “overwhelming.” He is very strict about limiting his client numbers so that he can give due care and attention, and says buyers who used to “not even know the definition of neurodivergent” now have a “readiness to do this.”

Welsh is a firm believer in the “purple pound” — the idea that one must make the business case for better representation as well as the moral one. “You have to show it makes business sense and is not just a good thing to do,” he says.

Comparable with Dyson, Welsh represents his clients in a traditional sense, but also advocates for their needs, taking a holistic approach. “If one of my actors is cast in a TV show then then we will always provide access consultancy on the script, for example, to ensure that the representation feels authentic,” he explains.

Paradigm shifts

Ruth Madely in Doctor Who

BBC Studios/Bad Wolf/Disney

Welsh is meeting with his company’s advisory board later this month to outline more ideas to grow the company, and says his biggest hope is “that there has been a paradigm shift from two years ago when this stuff was alien to people.”

Welsh, Roach, Johnson, Fernandez and others in this space are leaning in to this shift, pushing against that “disgusting” term floated by the Australian theatrical agent supremo Peggy Ramsay.

They are battling against the prejudices that have both overtly and covertly impacted the TV and film sector for decades, trying to imbue structure into an industry that has traditionally been built on informalities to the detriment of people from under-represented backgrounds. By normalizing such practices, training access co-ordinators and stressing the need for disabled people to be represented in a way that makes their condition incidental to a role, they hope to ride the sea change.

Dyson knows that it takes a group effort. She becomes “really angry” as she recalls a lack of “real action” from the people at the top during her three-decade tenure as a changemaker, which only makes her more determined. “There have been masses of initiatives, conference speeches and spotlighting with all the broadcasters, but what they fail to grasp is the need for a mechanism to make it happen,” she says. “My dream is that disability will be so integrated as to be completely unremarkable.”

And, with that, Dyson lays down a marker. The agent’s role will be crucial in the future of disabled talent.