The far-right rioters came for a hotel housing 130 asylum seekers. They laid siege to the grey Holiday Inn building in Yorkshire with bricks, chairs, and fire extinguishers, smashing open glass windows and marauding through corridors shouting obscenities at people who had fled their homelands for the sanctuary of Britain. Residents told The Times reporter Tom Witherow that they were terrified of being harmed. One shared a video of a rioter threatening to slit the throats of those in the building.

This was just one moment during six days of disorder in Britain this month. The riots were sprawling and sometimes messy in narrative, but sprung from the unthinkable stabbing of children at a Taylor Swift-themed dance class in Southport. The tragedy of that day was weaponized by online agitators who disseminated viral falsehoods about the alleged assailant being a Muslim asylum seeker. Elon Musk saw the anti-immigration rage and stoked it. TikTok and Telegram allowed it to fester on their platforms. The far-right’s online venom spilled onto the streets. South Asian residents feared for their safety.

The British screen industry was not immune from the unrest. TV journalists were caught up in the violence and major employers moved to prioritize staff safety, with the likes of Sky and Disney allowing people to work from home. Others signposted welfare support for employees from diverse backgrounds or made accommodations. Raise the Roof Productions, for example, provided a chaperone for Lubna Bhatti, a seasoned producer/director, during a shoot after she told superiors she was “afraid” to go to work.

“Stop the far-right” counter-protests in London

The disorder may have died down last Wednesday but it has provoked profound reflection among the UK film and television industry’s South Asian and Muslim communities, who have been forced to confront the specter of racism on their doorstep. Those watching in horror have asked: why are South Asians still consistently underrepresented and misrepresented on screen, and did these shortcomings help create the conditions for chaos?

“This is the culmination of years of dehumanizing brown people and the normalization of racist language and behaviors,” was the stark conclusion of Toral Dixit, a producer/director, who has worked on documentaries including BBC2’s Inside the Foreign Office and served on Directors UK’s diversity committee.

Deadline has spoken with more than a dozen South Asian men and women, representing all corners of the industry, to address some of these questions. The mood was raw, with some simply wishing to vent their exasperation with what they see as decades of industry failings and deeply damaging portrayals. Others want the riots to be a galvanizing moment akin to the Black Lives Matter movement, when racism was confronted and decision-makers were compelled to take action after years of talking. Most are pessimistic about the prospect of meaningful change.

Calling Islamophobia By Its Name

The news coverage of the riots themselves was at the forefront of the minds of those who spoke with Deadline. Many recognized the fraught and complex job of telling a story that stretched from Sunderland to Plymouth, but some saw tropes in TV reporting that made them uncomfortable. Several people referenced a debate on ITV’s Good Morning Britain, in which four white people cross-examined Zarah Sultana, a Labour MP and practicing Muslim, after she demanded that the government brand the riots Islamophobic.

Fatima Salaria, the former boss of The Apprentice UK producer Naked, spoke for many. “The reason why that triggered and resonated with so many people was that that was an example of what it feels like to be a brown person being questioned by a panel of white people about issues that speak to your lived experience,” says Salaria, executive chair of the Edinburgh TV Festival. “It’s the sneering remarks, the smirking, the eye-rolling, especially if you are from a working-class background and have not had the luxury of attending a debating club. It is an example of what it feels like to be a brown woman when you are having to justify your existence.”

Good Morning Britain’s exchange about Islamophobia — as well as presenter Ed Balls interviewing his wife, the home secretary Yvette Cooper — provoked 8,201 complaints to media regulator Ofcom, making it the second most complained about television moment of 2024. Ofcom is yet to commit to launching an investigation. ITV defended the show, arguing that it was “balanced, fair and duly impartial.”

Salaria was not alone in watching riot coverage and reflecting on experiences of prejudice. A drama director recalls being mistaken for a runner by a group of white executives, who asked if he could fetch them coffee. The same director says he was prevented from entering a set because security did not believe he was a senior member of the production. Kiren Dhadwal, a story producer who has worked on BAFTA-nominated Best Interests and EastEnders, remembers being called “street” by a senior producer.

Bhatti, a producer/director whose credits include Channel 4’s Love It Or List It and The Great British Bake Off, remembers being told by a drunk colleague at Vice that “Muslims are all terrorists.” She says Vice responded emphatically, apologizing, firing the employee, and offering her counseling, but says that the incident was revealing of a culture that allows people to speak openly about fearing Muslim people.

The failure to call Islamophobia by its name was a recurring theme in conversations with South Asian industry figures. Deadline reviewed several internal staff emails from broadcasters and producers last week as employers signposted welfare support. Most memos referenced racism, but only one labeled it Islamophobia. “We can’t just ‘tune out’ what is unfolding around us during working hours,” Channel 4 CEO Alex Mahon told employees. “This racist Islamophobic violence impacts how safe we feel.”

The UK government has no formal definition of Islamophobia, despite widespread support for a definition put forward by lawmakers of the all-party group on British Muslims. The MPs defined Islamophobia as being “rooted in racism… [and] a type of racism that targets expressions of Muslimness or perceived Muslimness.” Some say that without this definition, attempts to label Islamophobia fall at the first hurdle.

Ruhi Hamid, who has directed documentaries including BBC3’s Reggie Yates: Race Riots USA, says: “If Muslims are the perpetrators of violence, all the tropes are brought out relating to terrorism. But when Muslims are the victims, it feels as if it is ignored or silenced. The reluctance to even use the term Islamophobia is problematic.” A senior industry figure, who felt their job could be jeopardized by being named, put it more succinctly: “You don’t take a dictionary to a race riot.”

Far-right rioters in Sunderland

The platforming of figures like Nigel Farage compounds this feeling — particularly after the populist politician appeared on ITV’s I’m A Celebrity… Get Me Out Of Here! last year to the dismay of some industry creatives. The conflict in Gaza was held up as another complicating factor. One filmmaker, who wished to remain anonymous, says colleagues personally confronted him about the barbarism of October 7, but were “silent” when it came to the riots. Some argue that pro-Palestinian demonstrators have been painted as Hamas sympathizers. Hamid, the documentary director, believes it is more subtle: “Broadcasters are careful about not being sympathetic to Muslims in case they’re seen as lovers of Hamas. So there’s this kind of underlying self-censoring of how people respond to Muslims or matters of Islam.”

A Failure Of Nuance

Perceived shortcomings in coverage of the riots are a symptom of a decades-long failure by the British media to represent South Asian and Muslim communities in all their complexity, according to those interviewed. Waseem Mahmood is uniquely positioned to speak on this subject after he worked as a BBC producer; set up TV Asia, the first satellite service for the British Asian community; and received an OBE honor from Queen Elizabeth II for media reconstruction in post-war countries, including Afghanistan.

“What happened last week is the culmination of many years of demonizing Muslims. It was a tinderbox waiting to happen,” he says. “I’m in the autumn of my career and I am dismayed we are still having the same conversations. The UK hasn’t moved on. There needs to be a change of mindset [among decision-makers]; they can’t just sit back. Nobody is asking for positive representation, all we are asking for is fairer representation.”

Interviewees pleaded for more consistently nuanced portrayals. “Muslims are not one homogenized community, you would never say there’s one Christian identity. How can you speak about two billion people as one?” asks Mariayah Kaderbhai, head of programs at BAFTA. Adeel Amini, who produced CBS gameshow Lingo and founded freelance mental health group TV Mindset, puts it this way: “For want of a better phrase, I don’t think South Asians are sexy to people. People don’t understand the vastness of our culture.”

During a time when the industry has faced a diversity reckoning, representation of South Asians in British television has gone backwards, according to official figures from the Creative Diversity Network. The group’s Diamond diversity study showed that on and off-screen representation stood at 5.6% and 3% respectively in 2019. This dropped to 4.9% and 2.4% in the most recent study, with the latter being less than half the national UK average of 4.9%. Put simply, there are far fewer people of South Asian heritage making television than there should be.

The ‘Bodyguard’ Problem

Drama was seen as one of the worst offenders by many who spoke with Deadline. While comedies like the BBC’s Man Like Mobeen were exulted for their authenticity, there is a view that UK drama is the domain of white writers, producers, and directors, and this has damaged representation. A senior executive at a major broadcaster summed up the issues like this: “We’re still telling the same three stories: terrorism, a surrendered wife, or partition.”

Kaamil Shah, creator of ITV comedy Count Abdulla, argues that drama is in an “extremely unhealthy place.” In sharp contrast with his positive experience on Count Abdulla, Shah has been frustrated by drama script notes asking him to “push narratives” towards terrorism or honor killings. He explains that this has often been at the instruction of white executives keen to “raise the stakes” in a storyline or make it more “believable.” Similar issues are cited in unscripted. Amini recalls being told by a producer that a game show needed to cast a contestant who “looks more Muslim,” which he interpreted as an instruction to cast a woman in a hijab.

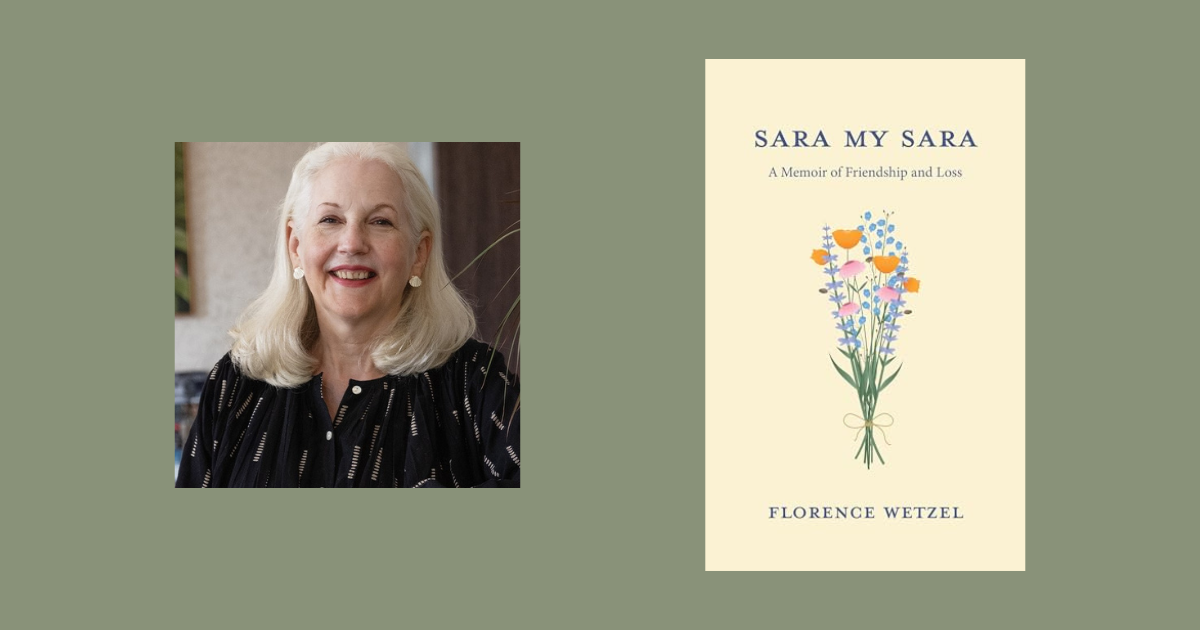

‘Bodyguard’

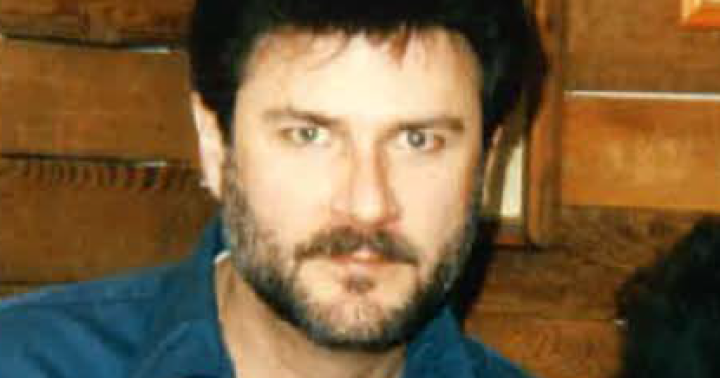

Several interviewees highlighted Bodyguard, the 2018 BBC and Netflix hit, as being particularly damaging because of its portrayal of Muslim character Nadia Ali (Anjli Mohindra) as both an oppressed woman and the mastermind behind terror plots. The series fails on nearly every measure of The Riz Test (named after Riz Ahmed), a set of five questions co-developed by University of Manchester academic Sadia Habib to assess whether Muslim characters fall into troubling tropes in film and TV. Bodyguard creator Jed Mercurio has previously defended creative choices, arguing that the “principal terror threats in the UK do originate from Islamist sympathizers.” He did, however, block critics on Twitter/X and has refused to answer questions on Muslim portrayal in his series, which was the most-watched in a decade when it premiered on the BBC.

More recent examples included Honour, the 2020 ITV series about the honor killing of Banaz Mahmod, which was written by Gwyneth Hughes, a white woman. A director, who did not wish to be named, says the trope of Muslims as “savages” continues to shape stories that get greenlit for the screen. “There’s no way in which we can, at the moment, take back control of certain stories because they’re uncommissionable.”

UK Muslim Film, which champions multifaceted Muslim representation, adds: “The impact of harmful stereotypes perpetuated by the screen industries cannot be overstated … It is crucial for our industry to recognize its role and accountability in shaping perceptions.”

The riots led to many calling on British commissioners to anchor stories about South Asian and Muslim communities in a historical context. Salaria, the former Channel 4 commissioner, argues that a quick win for the BBC would be to greenlight Once Upon A Time In The Middle East after the BAFTA-winning success of previous seasons about Iraq and Northern Ireland. Once Upon a Time in Space is the next iteration of the Keo Films show.

Shah, who suffered the “gutwrenching” cancelation of Count Abdulla after one season, thinks decision-makers should embrace period dramas that reflect Asian contributions to British history. Mahmood, the TV Asia co-founder, agrees. He was, until recently, talking to a major UK broadcaster about a feature film chronicling the life of Noor Inayat Khan, a British resistance agent who was executed in a Nazi concentration camp and posthumously awarded the George Cross for her service. Mahmood says the broadcaster rejected the film, citing its reluctance to greenlight a World War II story. Soon after, the same broadcaster commissioned a holocaust series featuring a majority white cast.

‘We Are Lady Parts’

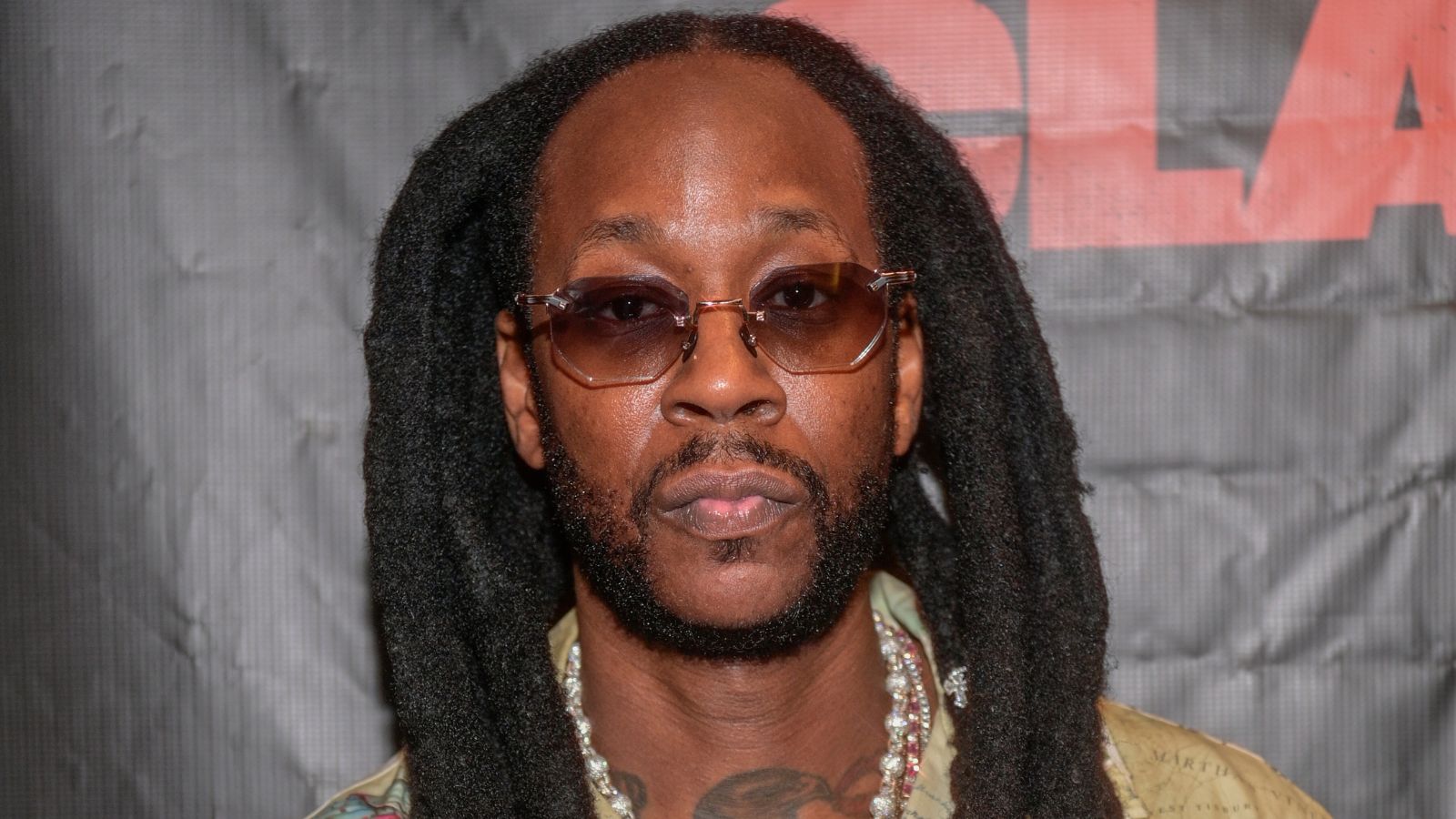

Interviewees did acknowledge examples of good practice. Nida Manzoor’s We Are Lady Parts, the BAFTA-winning Channel 4 comedy that streams on Peacock in the U.S., was universally lauded for its dazzling depiction of a Muslim punk band. Gurinder Chadha’s new feature Christmas Karma, a Bollywood take on A Christmas Carol, is highly anticipated. Others pointed to 2023 Race Across The World contestants Zainib Khan and Mobeen Qureshi. The duo became fan favorites after opening up about their fertility struggles and breaking bread with white strangers in rural Canada.

A Black Lives Matter Moment

Anyone familiar with the UK diversity debate will recognize the calls to action from South Asian creatives. For many who spoke with Deadline, it starts with representation among decision-makers and developing diverse talent into creative leadership roles. Short of this, people pleaded with white commissioners and producers to start listening to the lived experience of South Asians when telling stories about these communities. “The amount of times you see gatekeepers choosing white, middle-class males for jobs,” says Lubna, the former Vice worker. “I often think that if I had been chosen for certain jobs, I would have offered a different perspective, a different kind of [tonal] language that may have been more inclusive.”

There is also a feeling that diversity conversations have focused on the Black community for good reasons, but that this has had the unintended consequence of other global majority groups being overlooked. Amini says: “I would like to see industry leaders show this the same energy as they did for Black Lives Matter. This is as bad as it has ever been and if that can’t get people rallied behind us, as they have for other groups, that will be contributing to a lack of respect.”

Zainib Khan and Mobeen Qureshi on ‘Race Across the World’

There was, however, a deep sense of apathy about the appetite for change. “The industry has failed and it doesn’t even want to acknowledge that it’s failed,” says one person. Dhadwal, the story producer, adds: “There’s an infantilization of brown people. We are told that there are no brown writers who are big enough names. How can we get those names when we’re not given those opportunities? So it feels like we’re in a loop that we can’t get out of. It’s just so tiring.”

Broadcasters, studios, and producers may have moved swiftly to support South Asian and Muslim colleagues in the heat of the riots, but meaningful inclusion will require confronting more existential questions.